Red Dragon (1595)

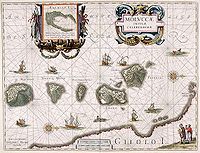

The Red Dragon, Captain Lancaster, in the Strait of Malacca, Anno 1602. | |

| Career (England) | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

Scourge of Malice (1595–1600) Red Dragon (1601–unknown) |

| Owner: | Earl of Cumberland (1595–1600) |

| Operator: | East India Company (1601–1619) |

| Builder: | Deptford Dockyard |

| Launched: | 1595 |

| Honours and awards: |

Participated in:

|

| Fate: | Sunk by Dutch fleet, 1619 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Armed ship |

| Tons burthen: | 600 – 900 tons |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Armament: |

38 guns[1]

|

Scourge of Malice or Malice Scourge or Mare Scourge was a 38-gun ship ordered by George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland. It was built and launched at Deptford Dockyard in 1595. The Earl used it as his flagship during raids on the Spanish Main, where it provided additional force to support his fleet. It was later renamed the Red Dragon and used by the East India Company during at least five voyages to the East Indies.

Construction

In the 1590s, the Earl of Cumberland's passion for nautical adventure was at its peak. He lacked a vessel able to support his hired fleet; the only option he had to get a sufficiently armed vessel was to borrow from the Queen, something which would give her significant control over his actions. As a result, he declared that he would have his own ship built, 'the best and largest ship that had been built by any English subject.'[2] The ship is variously recorded as being between 600[3] and 900[4] tons and was named by Queen Elizabeth I as Scourge of Malice.[2]

Service History

Raiding the Spanish Main (1595–1598)

Having had the Scourge of Malice built, the Earl then departed in his new ship, along with three smaller vessels, on another expedition to raid the Spanish Main.[4] However, the fleet had only travelled as far as Plymouth when he was recalled to London by the Queen.[4] He returned, leaving the remainder of the small fleet to continue without him.[2] On their return, he travelled out with them again; however on this voyage, the Scourge of Malice was badly damaged in a violent storm only forty leagues from England,[2] her mainmast being damaged,[4] and he was once more forced to return to seek repairs.[2]

With the repairs completed, the Earl set sail once again on 6 March 1598, the Scourge of Malice now the flagship of a fleet numbering twenty vessels.[2] After Sir Francis Drake's defeat at San Juan in 1595, the Earl of Cumberland was under orders to capture Brazil from the Spanish.[5] Following Drake's attack, the fort at San Juan was left with 200 men and 150 volunteers, bolstered by a further 200 men when reinforcements arrived from Spain.[5] By the time the Earl's fleet appeared off the coast of the islands on 16 June 1598, many of the Spanish soldiers had lost their discipline and turned to theft due to dysentery and the lack of food.[5] Two initial attacks by the English were fruitless, costing them lives without any gain; the Earl of Cumberland himself almost drowning trying to cross the San Antonio channel.[5] Knowing that the Spanish were short of supplies, the English preferred to lay siege to the castle of El Morro rather than destroy it, and on 29 June allowed the Spanish commander and troops to leave.[5] During the attack on the town, the English had only lost 200 men, but over the next two months they lost 400 to an epidemic of dysentery, and after occupying the island for only 65 days, Cumberland abandoned the fort.[6] Before they left, the English sacked the town, burning houses to the ground and stealing whatever caught their eye; items that included the cathedral bells and 2,000 slaves.[6]

The fleet continued to torment the Spanish settlements in the West Indies, achieving far more for Cumberland's country than his own wealth, from sale of his captures he only made about a tenth of the money that he had invested in the voyage.[2] The fleet lost two vessels and over a thousand men.[2]

East India Company, First Voyage (1601–1603)

Formed on 31 December 1600,[7] the East India Company's first voyage departed on 13 February 1601. The flagship of the five-vessel fleet was the Scourge of Malice, purchased from the Earl of Cumberland for £3700. On a more peaceful mission, the East India Company renamed the vessel the Red Dragon.[8] The other vessels in the fleet were the Hector (300 tons), Ascension (260 tons), Susan (240 tons) and the Gift, a small victualler.[9] In spite of their February departure, the fleet did not clear the English Channel until early April due to delays from contrary winds. They landed at the Canary Islands, and then, keeping too close to Africa, fell into the Doldrums, where they remained for a month. They replenished their provisions from a captured Portuguese vessel on route, but much of the fleet was affected by scurvy by the time they arrived at Table Bay on 9 September. Lancaster had managed to prevent his sailors from being so stricken by regularly dosing them with lemon-juice, and he was forced to send members of his own crew to help man the other ships. They stayed at Table Bay for seven weeks before departing, navigating along the eastern side of Madagascar. Since leaving England, they had lost more than a fifth of their crew complement across the fleet, but those that remained were fit and healthy. Adverse wind conditions, and a second bout of scurvy forced the fleet to drop anchor in Antongil Bay, where they remained from Christmas Day through until 6 March 1602. On the resumption of their journey, they reached the Nicobar Islands after two months further travel, and took the opportunity to take on water and trim their vessels, staying for three weeks.[10]

On 5 June, the fleet arrived in the road of Achin, on the northern end of Sumatra. There, Lancaster contacted the King, Ala-uddin Shah, who was delighted at the prospect of trade with the English, and granted them an exemption from customs dues. The goods at Achin failed to even fill one of the ships, and with the Susan having already been sent to Priaman to try and procure pepper and spices, Lancaster decided to target Portuguese vessels in the Strait of Malacca to increase his cargo.[11] The mission was successful, with Lancaster capturing a vessel on route from San Thomé (now part of Chennai) and transferring a large load of calicoes and other produce onto the English ships.[12] The fleet then returned to Achin on 24 October 1602 and collected King Ala-uddin Shah's reply to the Queen. The three ships left Achin on 9 November, and two days later the Ascension was despatched to return to England as it was fully laden. The Red Dragon and Hector sailed to Priaman, and Lancaster delivered instructions that when the Susan had finished loading her cargo of peppers and spices, she should set sail after the Ascension. Lancaster pressed his remained two vessels on towards Java, arriving at Bantam on 16 December. As in Achin, they presented a letter from Queen Elizabeth to the reigning monarch, and were granted permission to trade freely and "settle a factorie".[13] They traded all of their remaining English goods for almost 300 bags of peppers and set up an addition factory in the Moluccas before leaving.[14]

With a letter of reply from the King of Bantam, the two ships set sail on their return journey to England on 20 February. The return journey proceeded without incident until they had rounded the Cape of Good Hope, when they were caught in a heavy and sudden storm.[14] During the storm, the Red Dragon's rudder was broken off, leaving the ship at the mercy of the ocean.[15] The ship's carpenter tried to build an improvised rudder to try and steady the ship's course, but in the rough seas it provided no relief. In spite of his crew's pleas to transfer to the Hector, Lancaster insisted that the crew remain on the Red Dragon, telling his crew that they would "yet abide Gods leasure." Despite the confidence his showed his crew, he ordered the Hector to leave them and return to England.[16] When morning broke, the storm cleared as suddenly as it had appeared, and the Hector was not yet over the horizon; their captain having been reluctant to leave the Red Dragon while she was in distress.[17] Another new rudder was made, this time using wood from the mizzenmast, and the best swimmers and divers from the two ships hung it securely in place. After undergoing further repairs at St Helena, the Red Dragon and Hector eventually arrived back in England on 11 September 1603,[18] three months after the Ascension.[19] Lancaster was knighted, most likely upon his presentation of the letters from the Kings of Achin and Bantam, for his duties, but the profits from the voyage were minimal, the sheer quantity of goods making them hard to find buyers for.[20]

East India Company, Second Voyage (1604–1605)

The Second Voyage of the East India Company to the East Indies was made by the same four ships that had made the previous voyage, with the Red Dragon now under the command of Henry Middleton.[3] The fleet departed Gravesend on 25 March 1604 during the night, but when they stopped at the Downs, it was discovered that they were forty men short of their complement, and so had to wait for the remaining men.[21] On 1 April, the Red Dragon took on twenty-eight men, and despite this, Middleton was determined to set sail to make use of the beneficial wind conditions.[22] When a new muster of the men was taken, it was found that they were now twenty-eight men over their complement; and on contacting the other vessels, they found the same trend amongst them also.[23] Angry that he had lost use of a fair wind waiting for men he had not needed, and now would have to lose further use of it due to having to deposit those same men back to land, Middleton ordered that they should sail on to Plymouth and discharge the men there.[24] Despite these delays, the fleet passed Cabo da Roca on 7 April, and by 15 April had reached the Canary Islands.[24] They anchored at Maio, Cape Verde on 24 April, and set ashore in search of fresh food and water.[25] The following day, Middleton did not go ashore, but sent the three other captains to keep their men from straggling, an order reiterated by Captain Stiles, and then by master Durham.[26] They were due to set sail early the next morning, but before the anchor had been raised, Captain Stiles sent word to the Red Dragon that one of their merchants was missing; master Durham.[27] A search party numbering 150 men was sent out to search for him, but after a day's hunting failed to find the missing merchant, Middleton resolved to leave without him.[27]

The fleet crossed the equator on 16 May, and sighted the Cape of Good Hope just under two months later, the 13 July.[28] By this stage at least eighty of the Red Dragon's crew were suffering from scurvy, and although Middleton wanted to press on with the voyage and round the Cape, his crew protested and asked to put ashore to recover.[29] The weather played against them, and it was six days before they could get their sick on land.[30] Having landed at Table Bay, the company traded successfully with the local inhabitants, securing over two hundred sheep, a number of beeves, kine and a bullock.[31] On 3 August, the general (Middleton) took the Red Dragon's pinnace and a company of men in other boats to hunt whales in the bay.[32] The first harpoon to take a solid hold came from the pinnace of the Susan, which was then dragged up and down the bay for half an hour until they were forced to cut the rope to ensure their own safety.[33] The next shot that held came from the general's pinnace, and had this time struck a younger, littler whale.[33] As with the Susan's pinnace before it, the boat was towed back and forth the bay, while the larger whale stayed with them, harrying the boats with blows.[33] One such blow on the general's pinnace broke the timbers, causing the boat to flood and Middleton to take refuge on another of the boats.[33] With great difficulty, the pinnace was rescued and brought ashore where it took the ship's carpenters three days to repair.[33] Eventually the larger whale abandoned its ward, which took until sunset to die from its wounds, after which it was dragged to shore.[34] The oil from the whale was intended for their lamps, but a combination of the small size of the whale and bad casks provided the company with less than they would have liked.[35]

Following attacks from the native population, the fleet's company returned to their ships on 14 August, and then, with fair winds, set sail five days later.[36] On 21 December, the fleet anchored within the islands of Sumatra, having lost a number of men to scurvy, and with a number of those that remained weakened.[37] Due to illness, Middleton was unable to land and present the King of Bantam with a letter from King James I until 31 December.[38] It was then decided that the Red Dragon and Ascension would proceed to the Malucos, while the Hector and Susan would return to England with their cargoes.[38] The ships departed on 16 January, and just under a month later on 10 February made anchor off Ambiona; having lost a number of men to flux during their journey from Java.[39] Here they gained permission from the Portuguese commander to trade on the island.[40] Soon after their arrival however, a Dutch fleet arrived and took the fort by force, as a result of this the natives refused to trade with the English company until permission had been granted by the Dutch.[41] Middleton was now troubled, the Dutch were cutting off his opportunities to trade, in addition to Ambiona, they had also beaten the English to the Banda Islands, where they were offering the same commodities as the Red Dragon and Ascension had to offer.[42] In view of this, Middleton declared that the only way they could acquire the necessary quantity of goods was for the two vessels to split up, with the Red Dragon doing its best to go to the Malucos, while the Ascension made for the isles of Banda.[42] The decision was not well received among the crews of the two ships, due to the weakness they were suffering from due to dysentery, and the fact that travelling to the Malucos would mean sailing against both wind and current.[43] Despite these issues, the plan was carried out, the Red Dragon sailing for a month before sighting the Malucos.[44]

The company purchased fresh supplies from the people of Maquian, but the natives refused to trade or sell any cloves without permission from the king of Ternate. Duly, the Red Dragon sailed on towards Tidore and Ternate, more eastward islands. On 22 March, they became involved in a small fracas between Tidore and Ternate. Two Ternate galleys were rowing at best possible speed, hailing the Red Dragon to wait for them, being chased by seven Tidore galleys.[45] Middleton ordered the ship to slow and find out what was going on; they found that the galley contained the King of Ternate and three Dutch merchants. The Dutch pleaded with Middleton to rescue the second vessel, which contained more of their kinsmen who would be killed by the chasing Tidore. The Red Dragon fired at the Tidore galleys, but they maintained their course, and once within range, fired their own weapons at the trailing Ternate galley. They then boarded the vessel, killing all but three of the crew, those three having abandoned the vessel and swam to the Red Dragon.[46] In the aftermath of the attack, the Ternate King endeavoured to talk Middleton out of trading with their enemies on Tidore, and promoted the idea of setting up a factory on Ternate instead. Middleton was set on travelling to Tidore to trade with the Portuguese, saying that if they would not accept peaceable trade, he would have just cause to join the Dutch in war against them. They arrived at Tidore on 27 March, and the following day met Thomè de Torres, captain of one of the Portuguese galleon. The Red Dragon traded successfully and remained at Tidore for the next three weeks, acquiring all but 80 bahars[note 1] of the cloves on the island. The remaining cloves were unavailable as they belonged to merchants of Malacca.[47]

Accordingly, on 19 April, the Red Dragon prepared to depart for Maquian; an island mostly sworn to the king of Ternate, with the exception of the town of Taffasoa, which was sworn to the king of Tidore. Already in possession of a letter from the Ternate king, the Tidore king also wrote a letter asking the town's governor to trade with the English. With a Dutch fleet closing in on the island of Tidore, intending to take the island from the Portuguese, the Red Dragon departed two days later, needing to sound her trumpets as she passed the Dutch fleet at around midnight to identify herself, in case the Dutch thought she was an escaping Portuguese galleon. Safely past the Dutch, the ship and her crew arrived at Maquian at seven the following evening. On their arrival, Middleton sent his brother along with two Ternatans that had remained with the ship to present the governor with the king's letters. After a public reading of the letter, the governor announced that the cloves on the island were not ripe yet, but that those that were the English could have the next day. When the next day came however, they were told that there were no ripe cloves on the island, and Middleton, suspecting Ternatan duplicity, decided to sail for Taffasoa. They were more forthcoming, and the English managed to acquire an amount of cloves for them before the Ternate attacked the town. With the town's governor informing them that there were no more cloves to be had, and receiving word from the fort on Tidore that the Dutch had burnt two galleons, the Red Dragon returned to Tidore on 3 May.[48]

In addition to the Dutch fleet, the king of Ternate and all his caracoas were there, as part of the attack on their enemies. The Red Dragon received a cold reception from the Dutch, who claimed that a Guzerat had told them that they had assisted the Portuguese during the last battle, a claim the English vehemently denied. The Dutch then described the battle ensuing, and their plans to attack the fort on the next day. That evening Captain de Torres came aboard and told Middleton that they (the Portuguese) were sure of victory against the Dutch, and would trade any remaining cloves with the English. At around one in the afternoon on 7 May, the Dutch and Ternate attacked, firing all their ordnance at the fort. During particularly heavy fire, the attacking forces landed men on the island, a little north of the town, who entrenched themselves there for the night. The attack continued the next morning, and the landed men were now within a mile of the fort and set up a large piece of ordnance to further bombard the fort. The morning of 9 May, the attack began before sunrise, and catching the Portuguese unaware, the Dutch and Ternate scaled the walls and raised their colours in the fort. During the ensuing battle, the Portuguese and Tidorean forces got the upper hand and drove their enemies from the fort, forcing them to drop their weapons and retreat into the sea. Just as the battle seemed won, the fort exploded, and the combined Dutch and Ternatan forces rallied. The Portuguese retreated once more, sacking the town as they did so, burning the factory with the cloves and leaving nothing of worth.[49]

East India Company, Third Voyage (1607–10)

In August 1608, the Red Dragon headed for Java.[50] According to surviving transcripts of the ship's commanding officer, William Keeling, during their outward journey, they performed Hamlet twice and Richard II once.[50] Journals from the voyage exist, that of John Hearne and William Finch is held in the British Library, while that of Keeling has been lost, but extracts have been variously published.[51]

East India Company, Tenth Voyage (1612–14)

Under the command of Thomas Best, the Red Dragon took part in the tenth voyage of the East India Company, securing trading rights for the company at Surat in September 1612, and two months later engaging a Portuguese fleet and driving them from the Gulf of Cambay.[52] By January of the following year, he had set up a factory at Surat and extended trade to Ahmedabad, Burhanpur and Agra.[52]

East India Company, Voyage (1615–17)

The Red Dragon was again commanded by William Keeling during a voyage that also included the Lyon, the Peppercorn, and the Expedition which sailed from Tilbury on 3 February 1615.[53]

Sinking (1619)

In October 1619, the Red Dragon, commanded by Robert Bonner,[54] was attacked by a Dutch fleet and was sunk.[55] Captain Bonner was mortally wounded and died on 9 October.[54]

Ambiguity

Records of the voyages of the East India Company, including those made at the time, often refer to the Red Dragon simply as Dragon, familiarity resulting in the shortened title. This however can make tracing the history of the vessel more difficult. Although Sainsbury and Boulger both record the sinking of the vessel in 1619, a later reference is made to a ship named Dragon, commanded by John Weddell in 1637–38.[56] In Jean Sutton's Lords of the East; The East India Company and Its Ships, no fewer than four ships named Dragon are listed, and none named Red Dragon.[57] The first of these, listed as Dragon, 600 tons, 6 voyages, period of service: 1601–18 is almost undoubtedly the Red Dragon. The next ship chronologically is not until 1658, a vessel which undertook only one voyage,[57] leaving the identity of the vessel noted in the 1637–38 voyage unknown.

Notes

- ↑ Grey (1932), pp36–37.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Nichols (1823), pp496–497.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Corney (1855), p1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Southey (1834), pp33–34.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "SECOND ATTEMPT..... SIR GEORGE CLIFFORD (1598)". National Parks Service. http://www.nps.gov/archive/saju/saw10.html. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "1600: British for a while and other battles". Casiano Communications. 2000. http://www.coffeericeandbeans.com/print/CB1600.html. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ Vinay Lal. "The East India Company". University of California, Los Angeles. http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/History/British/EAco.html. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ↑ Foster (1933), p154.

- ↑ Foster (1933), pp154–155.

- ↑ Foster (1933), p155.

- ↑ Foster (1933), p156.

- ↑ Foster (1933), pp156–157.

- ↑ Foster (1933), p157.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Dulles (1969), p106.

- ↑ Dulles (1969), pp106–107.

- ↑ Dulles (1969), p107.

- ↑ Dulles (1969), pp107–108.

- ↑ Dulles (1969), p108.

- ↑ Foster (1933), p160.

- ↑ Foster (1933), pp161–162.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp1–2.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p2.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp2–3.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Corney (1855), p3.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp4–5.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p5.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Corney (1855), p6.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp6–7.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p7.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp7–8.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p9.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp9–10.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 Corney (1855), p10.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp10–11.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p11.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p14.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p15.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Corney (1855), p18.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp19–23.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp24–25.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp22–28.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Corney (1855), p28.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p29.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp29–33.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p33.

- ↑ Corney (1855), p34.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp34–45

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp46–50.

- ↑ Corney (1855), pp50–56.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Barbour (2008), p255.

- ↑ Kamps, Singh (2001), p211.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Riddick (2006), p127.

- ↑ Strachan and Penrose (1975), p237.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Sainsbury (1870).

- ↑ Boulger (1897), p23.

- ↑ "EAST MEETS WEST: Original Records of Western Traders, Travellers, Missionaries and Diplomats to 1852: Part 4". Adam Matthew Publications Ltd. http://www.adam-matthew-publications.co.uk/digital_guides/east_meets_west_part_4/Publishers-Note.aspx. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Sutton (1981), pp162–168.

References

Bibliography

- Barbour, Richmond (June 2008). "The East India Company Journal of Anthony Marlowe, 1607–1608". Huntington Library Quarterly (Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery) 71 (2): 255–301. ISSN 00187895. http://caliber.ucpress.net/doi/abs/10.1525/hlq.2008.71.2.255?cookieSet=1&journalCode=hlq. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh. The story of India (1897 ed.). London: H. Marshall & Son. http://www.archive.org/stream/storyofindia00bouluoft/storyofindia00bouluoft_djvu.txt.

- Corney, Bolton; Middleton, Sir Henry. The voyage of Sir Henry Middleton to Bantam and the Maluco Islands; being the second voyage set forth by the governor and company of merchants of London trading into the East-Indies (1855 ed.). London: Hakluyt Society. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RgA7AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Dulles, Foster Rhea. Eastward ho! The first English adventurers to the Orient (1969 ed.). Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 083691256X. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=wlsf8tQYLroC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Foster, Sir William. England's quest of eastern trade (1933 ed.). London: A. & C. Black. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Gp6wBJx0-igC&pg=PA154&lpg=PA154&dq=%22scourge+of+malice%22+ship&source=bl&ots=CdaJuGBHi_&sig=kcrI1Fih5n-7VEAk9Nsss0TQ310&hl=en&ei=maUNS7atEqKqjAeL4MzNAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CCUQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Grey, Charles. The Merchant Venturers of London : A Record of Far Eastern Trade & Piracy During the Seventeenth Century (1932 ed.). London: H.F.& G.Witherby.

- Kamps, Ivo; Singh, Jyotsna. Travel Knowledge: European "Discoveries" in the Early Modern Period (2001 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312222998. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=dAs0cGYzuZcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Nichols, John. The progresses and public processions of Queen Elizabeth : among which are interspersed other solemnities, public expenditures, and remarkable events during the reign of that illustrious princess : collected from original MSS., scarce pamphlets, corporation records, parochial registers, &c., &c. : illustrated with historical notes. 3 (1823 ed.). London: John Nichols and Son. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bicJAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Riddick, John F.. The history of British India: a chronology (2006 ed.). Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0313322805. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Es6x4u_g19UC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Sainsbury, W. Noel (1870). 'East Indies, China and Japan: May 1620'. Calendar of State Papers Colonial, East Indies, China and Japan, Volume 3: 1617-1621. pp. 367–375. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=68856. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- Sutton, Jean. Lords of the East; The East India Company and Its Ships (1981 ed.). London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851771696.

- Southey, Robert; Bell, Robert. The British admirals: With an introductory view of the naval history of England. 3 (1834 ed.). London: Printed for Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman (etc.). http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bzgJAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Strachan, Michael; Penrose, Boies. The East India Company Journals of Captain William Keeling and Master Thomas Bonner, 1615–17 (1975 ed.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "note", but no corresponding <references group="note"/> tag was found, or a closing </ref> is missing