SS United States

| |

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2009) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

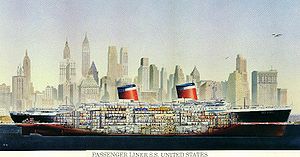

SS United States is a luxury passenger liner built in 1952 for the United States Lines designed to capture the trans-Atlantic speed record.

Built at a cost of $78 million,[4] the ship is the largest ocean liner constructed entirely in the United States, the fastest ocean liner to cross the Atlantic in either direction, and retains in her retirement the Blue Riband given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest speed.

Her construction was partially subsidized by the United States government, the ship was designed to allow conversion to a troop carrier should the need have arisen.[4] United States operated uninterrupted in transatlantic passenger service until 1969; since 1996 she has been docked at Pier 82 on the Delaware River in Philadelphia.

Contents

Construction

Inspired by the exemplary service of the British liners RMS Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, which transported hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops to Europe during the Second World War, the federal government of the United States decided to sponsor construction of a large and very fast vessel that would be capable of transporting large numbers of soldiers. Designed by renowned American naval architect and marine engineer William Francis Gibbs, the liner's construction was a joint effort between the United States Navy and United States Lines. The U.S. government underwrote $50 million of the $78 million construction cost, with the ship's operators, United States Lines, contributing the remaining $28 million. In exchange, the ship was designed to be easily converted in times of war to a troopship with a capacity of 15,000 troops, or a hospital ship.

The vessel was constructed from 1950-1952 at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Newport News, Virginia. The keel was laid and the hull was constructed in a graving dock. United States was built to exacting Navy specifications, which required the ship be heavily compartmentalized and have separate engine rooms to optimize war-time survival.

To minimize the risk of fire, the designers of United States used no wood in the ship's framing, accessories, decorations or interior surfaces. Fittings, including all furniture and fabrics, were custom made in glass, metal and spun glass fiber to ensure compliance with fireproofing guidelines set by the U.S. Navy. Though the galley did feature butcher block, the clothes hangers in the luxury cabins were aluminum. The ballroom's grand piano was of a rare, fire-resistant wood species, though originally specified in aluminum — and accepted only after a demonstration in which gasoline was poured upon the wood and ignited, without the wood itself igniting.

The construction of the ship's superstructure involved the largest use of aluminum in any construction project to that time, and presented a challenge to the builders in joining the aluminum structure to the steel decks below. The significant use of aluminum provided extreme weight savings. At 105 feet (32 m) beam, United States was built to Panamax capacity, ensuring the ship could clear the Panama Canal locks with just 2 feet (0.6 m) to spare on either side.

United States had the most powerful steam turbine in a merchant marine vessel. The ship was capable of steaming astern at over 20 kn (23 mph; 37 km/h), and could carry enough fuel and stores to steam non-stop for over 10,000 nautical miles (12,000 mi; 19,000 km).

Captains of United States included Harry Manning, Roy Edward Fiddler, John Anderson and Leroy J. Alexanderson.

Speed Records

On its maiden voyage on 4 July 1952, United States broke the transatlantic speed record held by Queen Mary for the previous 14 years by over 10 hours, making the maiden crossing from the Ambrose lightship at New York Harbor to Bishop Rock off Cornwall, UK in 3 days, 10 hours, 40 minutes at an average speed of 35.59 knots (40.96 mph) The liner also broke the westbound crossing record by returning to America in 3 days 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 knots (39.71 mph), thereby obtaining both the eastbound and westbound Blue Ribands — the first time a U.S. flagged ship had held the speed record since the SS Baltic claimed the prize a century earlier.

United States maintained a 30-knot (35 mph) crossing speed on the North Atlantic in a service career that lasted 17 years.

United States lost the eastbound speed record in 1990 — however, United States continues to hold the Blue Riband as all subsequent record breakers were neither in passenger service nor were their voyages east and westbound.[5]

The maximum speed of United States was deliberately exaggerated, and kept obscure for many years. An impossible value of 43 knots (49 mph) was leaked to reporters by engineers after the first speed trial.[6] The actual top speed — 38.3 knots (44.1 mph) — was not revealed until 1977. A Philadelphia Inquirer article reported the top speed achieved as 36 knots (41 mph),[7] while another source reports that the highest possible sustained top speed was 35 knots (40 mph; 65 km/h).[8]

Post-service

While United States was at Newport News for annual overhaul in 1969, the shipping line decided to withdraw the ship from service, docking the ship there. After a few years, the ship was relocated to Norfolk, Virginia. Subsequently, ownership passed between several companies. In 1978, the vessel was sold to private interests who hoped to revitalize the liner in a time share cruise ship format. Financing fell through and the ship was placed up for auction by MARAD. During the 1980s, United States was considered by the United States Navy as a troop ship or a hospital ship, to be called the USS United States, but this plan never materialized.

In 1984, the ship's remaining fittings and furniture were sold at auction in Norfolk. Some of the furniture now represents a substantial portion of the interior of Windmill Point, a restaurant in Nags Head, North Carolina.[9] These items include dining room tables and chairs in the main restaurant and the bar and lounge tables and chairs in the upstairs lounge as well as other items. One of the ship's propellers is mounted at the entrance to the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum in New York City. Another propeller is mounted on a platform near the waterfront at the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, NY. In 1992, a new consortium of owners purchased the vessel and had the vessel towed to Turkey and then Ukraine, where it underwent asbestos removal in 1994. No viable agreements were reached in the U.S. for a reworking of the vessel, and in 1996 United States was towed to its current location at Pier 84 in South Philadelphia. The ship is easily visible from shore and Interstate 95, directly across Columbus Boulevard from the Philadelphia IKEA store.

While United States lost the eastbound transatlantic speed record in 1990 to Hoverspeed Great Britain, an Incat-built Norwegian-owned wave-piercing catamaran ferry, it still holds the Blue Riband for the westbound transatlantic speed record.[4]

In 1999, the SS United States Foundation and the SS United States Conservancy (then known as the SS United States Preservation Society, Inc.) succeeded in having the ship placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Future plans

In 2003, Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) purchased the ship from the estate of Edward Cantor when the ship was put up for auction after his death, with the stated intent of fully restoring the ship to a service role in their newly-announced American-flagged Hawaiian passenger service called NCL America. The SS United States is one of only a handful of ships eligible to enter such service because of the Jones Act, which requires that any vessel engaged in domestic commerce be built and flagged in the USA and operated by a predominantly American crew. In August, 2004, NCL commenced feasibility studies regarding a new build-out of the vessel, and in May, 2006 Tan Sri Lim Kok Thay, chairman of Malaysia-based Star Cruises (which owns NCL), stated that the company's next project is "the restoration of the...United States."[10] By May, 2007, an extensive technical review had been completed, with NCL stating that the ship was in sound condition. The cruise line has over 100 boxes of the ship's blueprints cataloged. While this documentation is not complete, NCL believes it will provide useful information for the planned refit.[11] However, when NCL America began operation, it used Pride of America, Pride of Aloha, and Pride of Hawaii, rather than United States, and later withdrew Pride of Aloha and Pride of Hawaii from Hawaiian service.

In February 2009 it was reported that Star Cruises, to whom United States' ownership was transferred, and NCL were looking for buyers for the liner.[12][13]

A group of the ship's fans keeps in touch via the Internet and meets annually in Philadelphia. The ship receives occasional press coverage, such as a 2007 feature article in USA Today and there have been various projects through the years to celebrate the ship, such as lighting it on special occasions.[14] A television documentary about the ship entitled SS United States: Lady in Waiting was completed in early February, 2008 and was distributed through Chicago's WTTW TV and American Public Television with the first airings in May, 2008 on PBS stations throughout the USA.[15] The Big U: The Story of the SS United States, another documentary about the ship, is currently in development by Rock Creek Productions.[16]

It was reported in March 2010 that scrapping bids for the ship were being collected. Norwegian Cruise Lines, in a press release, noted that there are large costs associated with keeping United States afloat in her current state—around $800,000 a year—and that, as the SS United States Conservancy has not been able to tender an offer for the ship, the company was actively seeking a "suitable buyer."[17]

2009 - 2010 Rescue Efforts And Support

Ever since 2009 when Norwegian Cruise Line offered up the ship for sale there have been numerous plans to rescue the liner from the scrap yard.

The SS United States Conservancy, a group trying to save the ship from the scrapyard has been trying to come up with funding to purchase the ship.[18]

On July 30, 2009, H. F. Lenfest, a Philadelphia media entrepreneur and philanthropist, pledged a matching grant of $300,000 to help the United States Conservancy purchase the vessel from Star Cruises.[19]

A notable supporter, former US president Bill Clinton has also endorsed rescue efforts to save the ship having sailed on the ship himself in 1968.[20][21]

As of May 7, 2010 over $50,000 has been raised by The SS United States Conservancy [22]

On July 1, 2010, the Conservancy struck a deal with Norwegian Cruise Line to buy the ship from them for a reported $3 million dollars, despite a scrappers bid for $5.9 million. The Conservancy has until February 2011 to buy the ship and satisfy Environmental Protection Agency concerns related to toxins on the ship. They then have 20 months of financial support to develop a plan to clean the ship of toxins and make the ship financially self-supporting, possibly as a hotel or development in Philadelphia or New York.[23][1]

Gallery

- SS United States postcard.jpg

Postcard of the SS United States

- SSUnitedStates1964SunDeck.jpg

Sun deck of SS United States during 1964 eastbound voyage

- SSUnitedStates1964LeHavre.jpg

SS United States disembarking at Le Havre in 1964

- SS United States in Philadelphia.jpg

Photo of SS United States at Pier 84, Philadelphia, as viewed from Columbus Blvd

- SSUnited StatesMP.Jpg

Photo of the SS United States taken from The Spirit of Philadelphia cruise ship

- SS United States Fence.JPG

Another view of SS United States at Pier 84, as viewed from Columbus Blvd behind security fence.

See also

- SS America (1940), United States’s post-war running mate.

- SS Constitution

- SS Independence

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pesta, Jesse (1 July 2010). "Legendary Liner Steers Clear of Scrapyard". http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704334604575339053837359296.html?mod=googlenews_wsj. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ "World’s Fastest Superliner Awaits Rebirth—or the Scrap Yard" by Dan Koeppel, Popular Mechanics, June 2008.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23. http://www.nr.nps.gov/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Fans of World's Fastest Ocean Liner Put Out a Distress Call ... - - - ...". The Wall Street Journal, Jesse Pesta, 29 September 2009. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125417162355547323.html.

- ↑ Kludas, Arnold (1999). Record breakers of the North Atlantic, Blue Riband Liners 1838-1953. London: Chatham.

- ↑ "How Fast Can It Go? Paper on actual speed of SS United States; link now broken)

- ↑ SOS plan for faded ocean liner, Philadelphia Inquirer, August 24, 2009

- ↑ McKesson, Chris B., ed. (13 February 1998). "Hull Form and Propulsor Technology for High Speed Sealift" (PDF). John J. McMullen Associates, Inc.. pp. 13–14. http://www.ccdott.org/hss_volume2/05_high_speed_hulls_&_propulsors.pdf. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ↑ Pesta, Jesse (29 September 2009). "Fans of World's Fastest Ocean Liner Put Out a Distress Call". http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125417162355547323.html. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ Maritimematters.com

- ↑ John McDevitt (2007-05-09). "Cruising Future Seen For a Rusting South Phila. Hulk". KYW Newsradio, Philadelphia. http://www.kyw1060.com/pages/434964.php?contentType=4&contentId=481927.

- ↑ Niemelä, Teijo (2009-02-11). "SS United States may be offered for sale". Cruise Business Online. Cruise Media Oy Ltd. http://cruisebusiness.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=214%3Ass-united-states-may-be-offered-for-sale&catid=43%3Alatest-news-catecory&Itemid=111. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ "United States impending sale?". Maritime Matters. 2009-02-10. http://www.maritimematters.com/shipnews.html. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ Rick Hampson (3 July 2007). "Hopes dim for revival of SS United States". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-07-02-ss-united-states_N.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ "SS United States: Lady in Waiting". bigshipfilms. 2010. http://www.bigshipfilms.com/bsf_final/. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ "The Big U: The Story of the SS United States". The Big U. 2010. http://www.ssunitedstates-film.com/. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Ujifusa, Steven B. (March 3, 2010). "SS United States now in grave peril". PlanPhilly. http://planphilly.com/ss-united-states-grave-peril. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ "About". Ssunitedstatesconservancy.org. 2003-12-30. http://www.ssunitedstatesconservancy.org/SSUS/About.html. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ Moran, Robert (2009-07-30). "Phila. philanthropist to aid purchase of iconic ship". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia Newspapers LLC. http://www.philly.com/inquirer/local/20090730_Phila__philanthropist_to_aid_purchase_of_iconic_ship.html. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ "SS United States Trust". SS United States Trust. 2009-07-04. http://www.ssunitedstatestrust.org/. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ "SS United States Documentary Film - The Big U". Ssunitedstates-film.com. 1969-11-07. http://www.ssunitedstates-film.com/history.html. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ "Fund Aims To Save S.S. United States". Myfoxphilly.com. http://www.myfoxphilly.com/dpp/good_day_philadelphia/SS_United_States_Fundraising_050710. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ "Preservationists Perched To Buy SS UNITED STATES | MaritimeMatters | Cruise ship news and ocean liner history". MaritimeMatters. http://maritimematters.com/2010/06/preservationists-perched-to-buy-ss-united-states/. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

Further reading

- Braynard, Frank O. (1968). By Their Works Ye Shall Know Them, The Life and Ships of William Francis Gibbs 1886-1967. New York: Gibbs & Cox, Inc. OCLC 1192704.

External links

- Big Ship Films, LLC's Homepage about the Lady In Waiting Documentary

- "The United States" by C.K. Williams

- Archival film footage of a cruise aboard the SS United States

- SS United States Conservancy

- SS United States Foundation a Federal 501c3 nonprofit historic preservation site

- SS United States site

- SS United States 2007 photographs

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Queen Mary |

Holder of the Blue Riband (westbound) 1952 – present |

Incumbent |

| Atlantic Eastbound Record 1952 – 1990 |

Succeeded by Hoverspeed Great Britain | |

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

da:SS United States (1952) de:United States (Schiff) es:SS United States fr:United States (paquebot) hr:SS United States it:SS United States nl:United States (schip) ja:ユナイテッド・ステーツ (客船) no:SS «United States» pl:SS United States ru:SS United States

- Pages with broken file links

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Articles needing additional references from July 2009

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles needing additional references

- IMO Number

- Ocean liners

- Steamships of the United States

- National Register of Historic Places in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Blue Riband holders

- Passenger ships of the United States

- Ships built in Virginia

- Ships on the National Register of Historic Places

- 1952 ships

- Type P6 ships