Diosa del Mar

The Diosa del Mar (Spanish: Goddess of the Sea) was a wooden schooner that sank off of the coast of Catalina Island at 2:25 pm on July 30, 1990.

Overview

The two masted wooden schooner was designed by A. Cary Smith and built in 1898 by the firm of A.C. Brown and Sons of Tottenville, NY. It was originally christened Uncas after the famous chief of the Mohegan tribe. Through various owners, the name was subsequently changed to Wal Gar, Bonnie Doone, and finally Diosa del Mar. In Lloyd's Register of American Yachts it appears as Bonnie Doone until finally disappearing from the registry in 1959 under the ownership of a Dr. Irving E. Laby in Los Angeles, California.

The yacht was originally built as a staysail craft for the children of the wealthy Vanderbilt clan. As originally built she weighed 30 tons, was 66 feet 6 inches (20.27 m) long, had a total sail area of 3,321 square feet (308.5 m2), and a draft of 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m). The Diosa was perfectly capable of deep ocean travel. Following the installation in 1916 of a Sterling gas engine, the vessel's capabilities were quite advanced. By 1925 she sported a full keel (modified from her original keel with auxiliary centerboard) and a GM Diesel engine.

According to Lloyd's, the Diosa was burned and rebuilt in 1927. By 1951 she had been refitted with a 6-cylinder Chrysler engine and was operating out of Balboa, California.

In 1979 she won the Serena Cup as the fastest schooner in the Newport to Ensenada Race (California to Mexico). Subsequently, she sailed from Los Angeles to Hilo, Hawaii where she operated as a charter until 1982. After returning to Los Angeles, she placed second place in the Newport to Ensenada race of 1983. For most of the rest of her life she operated as a charter out of Long Beach, California.

The yacht's demise came about near the end of the 10th annual Firemen's Race in 1990 off the coast of southern California. A small powerboat failed to spot the racing Diosa. The powerboat hove out of the Isthmus of Catalina, cutting in front of the doomed ship. Rather than risk injury or death to the driver and passengers on the smaller craft, Diosa's owner and captain Eddie Weinberg steered hard to starboard crashing his ship against Ship Rock[1] The wreckage of the schooner was a favorite of divers for many years before finally breaking up beneath the waters of the Pacific Ocean.

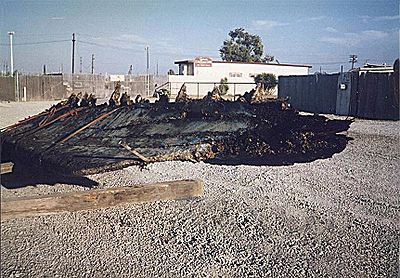

The salvaged stern and mast from the Diosa Del Mar was on display at the Isthmus on Catalina Island, California for a number of years.

Spot Where the Diosa del Mar Sank (Ship Rock)

The salvage of the keel was done by Don and Ed Huseman.

Diosa del Mar is located at 33°27′46″N 118°29′31″W / 33.462770°N 118.491925°WCoordinates: 33°27′46″N 118°29′31″W / 33.462770°N 118.491925°W.

Ship Rock is located 3 miles east of the Isthmus on Catalina Island, California.

Numerous people over the years, since the sinking of the Diosa Del Mar in 1990 had attempted to raise and salvage the keel of the boat. It took two attempts by the Huseman brothers, and about 17 trips to Catalina to move masts and debris in preparation to raise the keel off the rocks and reef, and towed to Long Beach Harbor, California. The eventual successful salvaging operation in 1993 was "the talk" of the maritime groups and the news media in the Los Angeles Basin, since there had been so many failed attempts over the years.

The Huseman brother's first trip to Catalina Island was to survey the keel wreckage and the placement in the rocks and reef at Ship Rock. They also discovered that the size of the keel was not as large as they had originally estimated. At first, they thought the keel would weigh about 100,000 lbs (50 tons), but after examining the keel during a dive, and making the calculations it turned out to be only about 40,000 pounds (20 tons). The salvage of the 20-ton keel was for the scrap lead value.

On the first attempt to raise the keel, Gordon Frappier towed a 30-foot-long (9.1 m) by 8-foot-diameter (2.4 m) empty gas tank from the California mainland over to the wreck site next to Ship Rock, three miles from the Isthmus on Catalina Island. The reason the tank was used for lifting vs individual lift bags, was the tank was easier to control, and the least expensive means instead of using a multitude of lift bags for the 20-ton keel. After extensive preparations, the tank fitted with chains was floated and positioned over the keel. The tank was filled with water and submerged, then connected to the big turnbuckles and the bronze bolts sticking out of the top of the keel. The divers performed this connection at low tide, then waited for high tide to float the keel and the tank off the rocks, at about 12 ft deep (3.7 m). When the tide came in, the surge was very strong, and the 20-ton keel and tank swayed back and forth. The bronze nuts on the keel didn't like to bend, and the 1.25-inch (32 mm) keel studs broke off and the tank floated to the surface, thus ending their attempt.

The second time they attempted to raise the keel, the same tank was used and the tide was not used for leverage. Ed Huseman positioned the tank over the keel and flooded the tank with water to submerge the tank, and then attached the tank to the keel. The next process was to blow out the water in the tank with the attached keel, and then the two would float to the surface. Ed Huseman figured out that hooking ten air tanks together, containing 72 cubic feet (2.0 m3) of air and attaching a garden hose from the air tanks to the tank's top valve, the air at the top would force the water out through the bottom of the tank. Ed Huseman's ingenious idea worked very well. The air blew the water out of a 30-foot-long (9.1 m) x 8-foot-diameter (2.4 m) tank in about 30 minutes. The keel and the tank floated up to about 4 feet (1.2 m) off the reef, however there were rocks about 5 ft high (1.5 m) that blocked the exit movement of the keel. They tried to pull the tank and keel out one way, but the towboat, a Cal 39 sail boat with a Perkins 4108 50-hp diesel engine, skippered by Dan Cohen, was too far away to tell Cohen that the keel was still stuck in the rocks, and the tow rope snapped into two pieces.

After being in the water for over nine hours that day, the four divers almost gave up. One of the divers, Steve Stiener, said they could move the keel, and they were able to push the tank with just flipper power. The divers all felt that the tank and keel were going to hit more rocks, however the keel and tank moved out of the rock and reef area, went through a bed of seaweed and into dark deep water, and floated to the water's surface. After the broken tow rope was repaired, Cohen started towing the tank and keel out of the rock and the reef area. The exhausted diving crew, after being in the water for two days, and the sailboats left Catalina Island elated, having achieved a successful salvage operation that no one else had been able to accomplish. The tank and 20-ton keel were then towed 24 miles by the Cal 39 Perkins 4108 50-hp diesel engine across the Catalina Channel to Long Beach Harbor.

File:Floating Tank.jpg Tank with attached keel on the water's surface. |

File:Leaving Catalina.jpg Tank and keel in tow - Catalina Isthmus in the background. |

File:Tank and keel at Long Beach.jpg Tank and keel at Long Beach Harbor, California. |

Sources

- Lloyd's Register of American Yachts (still listed in 1917 as Uncas; from 1925 through 1959 as Bonnie Doone)

- Diosa del Mar at California Wreck Divers (some incorrect spellings) (retrieved April 14, 2008)

- "Shipwrecks off the coast of California" by Gregory J. Robb (retrieved May 24, 2007)

- Color photos - by Susan Macafee

References

- ↑ Carlton J (August 01 1990). "Coast Guard Investigates 1898 Schooner's Sinking". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1990-08-01/news/mn-1558_1_coast-guard.