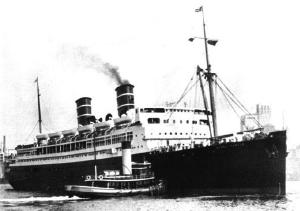

SS Morro Castle (1930)

| |

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Morro Castle |

| Owner: | Ward Line |

| Route: | New York City to Havana, Cuba |

| Builder: | Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company |

| Cost: | $4 million in 1930 |

| Christened: | March 1930 |

| Completed: | 15 August 1930 |

| Maiden voyage: | 23 August 1930 |

| Fate: | Caught fire and beached on 8 September 1934 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 11,520 gross |

| Length: | 508 feet (155 m) |

| Beam: | 71 ft (22 m) |

| Propulsion: | steam turboelectric drive, twin propellers |

| Speed: | 20 knots (37 km/h) |

| Capacity: | 489 passengers |

| Crew: | 240 crew |

The SS Morro Castle was a luxury cruise ship of the 1930s that was built for the Ward Line for runs between New York City and Havana, Cuba. The Morro Castle was named for the Morro Castle fortress that guards the entrance to Havana Bay.

In the early morning hours of Saturday, 8 September 1934, en route from Havana to New York, the ship caught fire and burned, killing a total of 137 passengers and crew members. The ship eventually beached herself near Asbury Park, New Jersey and remained there for several months until she was eventually towed away and sold for scrap.

The devastating fire aboard the SS Morro Castle was a catalyst for improved shipboard fire safety. Today, the use of fire retardant materials, automatic fire doors, ship-wide fire alarms, and greater attention to fire drills and procedures resulted directly from the Morro Castle disaster.

Contents

Construction of the SS Morro Castle

In the spring of 1928, the U.S. Congress approved a Merchant Marine Act that created a $250 million construction fund that would be loaned to American steamship companies so that they might replace their old and outdated ships with new ones. Each of these loans, which could subsidize as much as 75% of the cost of the ship, was designed to be paid back over twenty years at very low interest rates. One company that quickly availed itself of this opportunity was the Ward Line (officially: the New York and Cuba Mail Steam Ship Company), which had been carrying passengers, cargo and mail to and from Cuba since the mid 1800s. Naval architects were hired by the line to design a pair of cruise and cargo ships to be named the SS Morro Castle (after the stone fortress and lighthouse in Havana) and the SS Oriente (after a province in Cuba).

At the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, work was begun on the SS Morro Castle in January 1929. In March 1930, the SS Morro Castle was christened, followed in May by her sister ship, the SS Oriente. Each ship was 508 feet long, measured 11,520 gross tons, and was luxuriously finished to accommodate 489 passengers in first and tourist class, along with 240 crew members and officers. The cost of each ship was estimated at approximately $5 million.[citation needed]

Four successful years

The SS Morro Castle's maiden voyage began on 23 August 1930. She lived up to expectations by completing the maiden 1100+ mile southbound voyage in just under 59 hours, while the return leg took only 58 hours. In the four years that followed, the Morro Castle and Oriente were luxury ship workhorses, rarely out of service and, despite the worsening of The Great Depression, able to maintain a steady clientele. Their success was in part due to Prohibition, as such trips provided an affordable and (more importantly) legal means of enjoying a nonstop drinking party. However, their reasonable rates also attracted Cuban and American businessmen and older couples, making the ship a proverbial microcosm of America. Like cruise ships of today, food on board the ship was both plentiful and diverse.[citation needed]

Disaster strikes the SS Morro Castle

The final voyage of Morro Castle began in Havana on 5 September 1934. On the afternoon of the 6th, as the ship paralleled the southeastern coast of the United States, it began to encounter increasing clouds and wind. By the morning of the 7th, the clouds had thickened and the winds had shifted to easterly, the first indication of a developing nor'easter. Throughout that day, the winds increased and intermittent rains began, causing many to retire early to their berths. Early that evening, Captain Robert Willmott had his dinner delivered to his quarters. Shortly thereafter, he complained of stomach trouble and, not long after that, died of an apparent heart attack. Command of the ship passed to the Chief Officer, William Warms. During the overnight hours, the winds increased to over 30 miles per hour as the Morro Castle plodded its way up the eastern seaboard.

At around 2:50 a.m. on September 8, while the ship was sailing around eight nautical miles off Long Beach Island, a fire was detected in a storage locker within the First Class Writing Room on B Deck. Within the next 30 minutes, the Morro Castle became engulfed in flames. As the fire grew in intensity, Acting Captain Warms attempted to beach the ship, but the growing need to launch lifeboats and abandon ship forced him to give up this strategy. Within 20 minutes of the fire's discovery (at approximately 3:10), the fire burned through the ship's main electrical cables, plunging the ship into darkness. As all power was lost, the radio stopped working as well in which the crew were cut off from radio contact after issuing a single SOS transmission. At about the same time, the wheelhouse lost the ability to steer the ship, as those hydraulic lines were severed by the fire as well.[1]:40 Cut off by the fire amidships, passengers tended to gravitate toward the stern. Most crew members, on the other hand, moved to the forecastle.[1]:48 On the ship, no one could see anything. In many places, the deck boards were hot to the touch, and it was hard to breathe through the thick smoke. As conditions grew steadily worse, the decision became either "jump or burn" for many passengers. However, jumping into the water was problematic as well. The sea, whipped by high winds, churned in great waves that made it extremely difficult to swim.

On the decks of the burning ship, the crew and passengers exhibited the full range of reactions to the disaster at hand. Some crew members were incredibly brave as they tried to fight the fire. Others tossed deck chairs and life rings overboard to provide persons in the water with makeshift flotation devices.[1]:50 Only six of the ship's 12 lifeboats were launched -- boats 1, 3, 5, 9 and 11 on the starboard side and boat 10 on the port side. Although the combined capacity of these boats was 408, they carried only 85 people, most of whom were crew members. Many passengers died for lack of knowledge on how to use the life preservers. As they hit the water, life preservers knocked many persons unconscious, leading to subsequent death by drowning, or broke victims' necks from the impact, killing them instantly.[1]:58

The rescuers were slow to react. The first rescue ship to arrive on the scene was the SS Andrea F. Luckenbach. Two other ships — the SS Monarch of Bermuda and the SS City of Savannah — were slow in taking action after receiving the SOS, but eventually did arrive on the scene. A fourth ship to participate in the rescue operations was the SS President Cleveland, which launched a motor boat that made a cursory circuit around the Morro Castle and, upon seeing nobody in the water along her route, retrieved her motor boat and left the scene.

The Coast Guard vessels Template:USCGC and Template:USCGC positioned themselves too far away to see the victims in the water and rendered little assistance. The Coast Guard's aerial station at Cape May, New Jersey failed to send their float planes until local radio stations started reporting that dead bodies were washing ashore on the New Jersey beaches from Point Pleasant Beach to Spring Lake.

In time, additional small boats arrived on the scene. The major problem was that in the large ocean swells, it was very difficult to see people in the water. A plane piloted by Harry Moore, Governor of New Jersey and Commander of the New Jersey Guard, helped boats locate survivors and bodies by dipping its wings and dropping markers.[1]:98

As news of the disaster spread along the Jersey coast by telephone and radio stations, local citizens assembled on the coastline to retrieve the dead, nurse the wounded, and try to unite families that had been scattered between different rescue boats that landed on the New Jersey beaches.

By mid-morning, the ship was totally abandoned and its hull drifted ashore, coming to a stop in shallow water off Asbury Park, New Jersey late that afternoon where the fires smoldered for the next two days. In the end, 135 passengers and crew (out of a total of 549) were lost. The ship was declared a total loss, and its charred hulk was finally towed away from the Asbury Park shoreline on 14 March 1935 to be sold for scrap. In the intervening months, because of its proximity to the boardwalk and the Asbury Park Convention Center pier, from which it was possible to wade out and touch the wreck with one's hands, it was treated as a destination for sightseeing trips, complete with stamped penny souvenirs and postcards for sale.[2]

Factors contributing to the fire

The design of the ship, the materials used in its construction, and questionable crew practices and mistakes escalated the on-board fire to a roaring inferno that would eventually destroy the ship.

As far as the materials used in the ship's construction were concerned, the elegant (but highly flammable) decor of the ship - veneered, wooden surfaces and glued, ply paneling - helped the fire to burn quickly.[1]:54

The structure of the ship also created a number of problems. Although the ship had fire doors, there existed a wood-lined, six-inch opening between the wooden ceilings and the steel bulkheads. This provided the fire with an flammable pathway that bypassed the fire doors, enabling it to spread.[1]:169 Whereas the ship had electric sensors that could detect fires in any of the ship's staterooms, crew quarters, offices, cargo holds and engine room, there were no such detectors in the ship's lounges, ballroom, writing room, library, tea room, or dining room.[1]:10 Although there were 42 water hydrants on board, the system was designed with the assumption that no more than six would ever have to be used at any one time. When the emergency aboard the Morro Castle occurred, the crew opened virtually all working hydrants, dropping the water pressure to unusable levels everywhere.[1]:44 The ship's Lyle gun, which is designed to fire a buoy to another ship to facilitate passenger evacuation in an emergency, was stored over the Morro Castle's writing room, which is where the fire originated. The Lyle gun exploded just before 3 a.m., further spreading the fire and breaking windows, thereby allowing the near-gale-force winds to enter the ship and fan the flames.[1]:39 Finally, fire alarms on the ship produced a "muffled, scarcely audible ring" according to passengers.[1]:39

Crew practices and deficiencies added to the severity of the on-board fire. According to surviving crewmen, painting the ship had been a common practice to keep it looking new and to keep crewmen busy. Unfortunately, the thick layers of paint that resulted from this practice made the ship more flammable and strips of paint broke off during the fire, helping to spread the flames.[1]:50 The storage locker in which the fire started held blankets that had been dry cleaned using 1930s technology, which utilized flammable dry cleaning fluids[1]:32 (although it is unlikely that significant amounts of the fluid would remain). Although the ship had fire doors, their automatic trip wires (designed to close when a certain temperature was reached) had been disconnected. None of the crew thought to operate them manually at the time of the fire. That said, it really wouldn't have mattered, since the six-inch opening between the wooden ceilings and the steel bulkheads would have allowed the flames to spread even if the fire doors had closed.[1]:151 Many of the hose stations on the promenade deck had been recently deactivated in response to an incident about a month before when a passenger slipped on a deck moistened by a leaking hose station and sued the cruise line.[1]:18 Although regulations required that fire drills be held on each voyage, only the crew members participated. Passengers were not required to attend.[1]:40 For quite some time after the fire was discovered, the ship continued on its course and speed pointed directly into the wind. This no doubt helped to fan the fire. In an attempt to reach passengers in some suites, crewmen broke windows on several decks, allowing the high winds to enter the ship and hasten the fire's fury.[1]:40 Because the wireless operators couldn't get a definitive answer from the captain, the SOS wasn't ordered until 3:18, and wasn't sent until 3:23. Within five minutes, the intense heat of the fire began to distort her signal. Shortly thereafter, emergency generators failed and transmissions ceased.[1]:45

Aftermath

In the inquiries that followed the disaster, there were criticisms of the response of the first officer's handling of the ship, the crew's response to the fire, and delay in calling for assistance.

The inquiries concluded that there was no organized effort by the officers to fight and control the fire or close the fire doors. The crew made no effort to take their regular fire stations. More damning was the conclusion that, with a few notable exceptions, the crew made no effort to direct passengers to safe pathways to the boat deck. For many passengers, the only course of action was to lower themselves into the water or jump overboard. The few lifeboats that were launched carried primarily crew, and no efforts were made by these boats to maneuver toward the ship's stern to pick up additional people.[1]:162

The newly promoted Captain Warms never left the bridge to determine the extent of damage and maintained the ship's bearing and full speed for some distance after the fire was known. As systems failed throughout the ship because of power loss, no effort was made to use the emergency steering gear or emergency lighting.[citation needed]

Warms, Chief Engineer Eban Abbott, and Ward Line vice-president Henry Cabaud were eventually indicted on various charges relating to the incident, including willful negligence. All three were convicted and sent to jail. However, an appeals court later overturned Warms's and Abbott's convictions, deciding that a fair amount of the blame could be attributed to the dead Captain Willmott.[citation needed]

In the inquiry that followed the disaster, Chief Radio Operator George Rogers was made out to be a hero because, having been unable to get a clear order from the bridge, he sent a distress call on his own accord amidst life-threatening conditions. Later, however, suspicion was directed at Rogers when he was convicted of attempting to murder his police colleague with an incendiary device. His crippled victim, Vincent 'Bud' Doyle, spent the better part of his life attempting to prove that Rogers had set the Morro Castle fire as well. In 1954, Rogers was convicted of murdering a neighboring couple for money, and he died three and a half years later in prison.[citation needed]

The New York Times reported the end of the inquiry on 27 March 1937 with an order by Federal Judge John C. Knox affixing liability at $890,000, an average of $2,225 per victim.[citation needed] About half the claims were for deaths. It was reported that the order included agreement by 95% of the claimants. The order also barred further claims against the steamship company and its subsidiary, the Agwi Steamship lines, operators of the vessel. Several months work remained in deciding each claim individually by the lawyer members of the Morro Castle Committee. Damages were fixed under the Death on the High Seas Act.

Officially, the cause of the fire was never determined. In the mid-1980s, HBO television aired a dramatization of the fire in their Catastrophe series, called "The Last Voyage of the Morro Castle." The dramatization starred John Goodman as Radio Officer George Rogers, and blamed Rogers for causing the fire. In 2002, the A&E television network made a documentary about the incident. Both the HBO dramatization and the A&E documentary rekindled speculation that the fire was actually arson committed by a crew member. Other theories included a short circuit in the wiring that passed through the rear of the locker, the spontaneous combustion of chemically treated blankets in the locker, or an overheating of the ship's one functioning funnel, which was located just aft of the locker.[1]:178

William McFee, a well-known writer of sea stories who had served as an engineer on oil-fired steamers, wrote in 1949 that "if the burners were neglected" the "long uptakes which lead from the furnaces to the funnel would become dangerously overheated," as he once found on another ship, whose "funnel was glowing red-hot just above the uptakes." The Morro Castle's funnel was clad in flammable material where it passed through the passenger quarters, and smoke had been noticed by several people as early as midnight. The ship was making 19 knots against a 20-knot headwind and simply overheated, according to McFee, but the high loss of life was caused by the crew's incompetent handling of the emergency. [3]

Irrespective of its cause, the fire aboard the SS Morro Castle served to improve fire safety for future ships. The use of fire retardant materials, automatic fire doors, ship-wide fire alarms, the necessity of emergency generators, mandatory crew training in fire fighting procedures, and greater attention to fire drills and procedures resulted directly from the Morro Castle disaster.

Some victims of the fire are buried in the Mount Prospect Cemetery located in Neptune, New Jersey, located nearby along the coast.[4]

Due to the great loss of life the disaster caused, many reforms in the licensing of merchant marine officers occurred, such as the establishment of the United States Merchant Marine Academy.

Despite the fascinating tragedy and mystery of the Morro Castle Disaster, no film for theatrical distribution nor even a television movie was made of the story. However there have been references to it. In the 1938 film Boy Meets Girl, James Cagney (in dictating a letter to Pat O'Brien regarding what a third person is supposed to be saying to his missing wife) says, "I did not go down on the Morro Castle!" At the conclusion of the 1935 Spencer Tracy film Dante's Inferno a gambling cruise ship (resembling the Morro Castle) is completely ablaze. An exploitative mention in the 1942 detective film The Man Who Wouldn't Die is that one suspect was assumed to have perished on this ship, but who survived unbeknownst to another. The 1944 movie Minstrel Man also features the fire and sinking of the Morro Castle. In 1970 the West Coast music critic Philip Elwood described the early Bruce Springsteen-led, and Asbury Park-based, Steel Mill as "the first big thing that's happened to Asbury Park since the good ship Morro Castle burned to the waterline of that Jersey beach in '34."

Curiously, the Morro Castle's radio call sign, KGOV, is still registered to the ship by the FCC over 70 years after her demise, and is therefore unavailable for use by broadcast stations. [5]

On September 8, 2009, the first and only memorial to the victims, rescuers and survivors of the Morro Castle disaster was dedicated on the south side of Convention Hall in Asbury Park, NJ, very near the spot where the burned-out hull of the ship finally came aground. The day marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the disaster.[6]

See also

- SS Yarmouth Castle

- SS Noronic

- General Slocum

- RMS Queen Elizabeth

- SS Normandie

- Star Princess

- Herbert Saffir - a survivor of the Morro Castle

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Burton, Hal (1973), The Morro Castle: Tragedy at Sea, New York: Viking Press, ISBN 0670489603

- ↑ Thurber, James (November 17, 1934), "Excursion", The Beast in Me and Other Animals, New York: Harcourt, Brace (published 1948), pp. 332, ISBN 0151112495, OCLC 290331

- ↑ William McFee, "The Peculiar Fate of the Morrow Castle," The Aspirin Age, Penguin Books, 1949, p. 344

- ↑ Shields, Nancy (September 12, 2008), "Historian Disputes Shipwreck Burial Claim", Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, NJ: Gannett Co.), OCLC 16894042, archived from the original on or before January 10, 2010, http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/app/access/1696876571.html?FMT=ABS&date=Sep+12,+2008

- ↑ White, Thomas H. (January 1, 2010). "Mystique of the Three-Letter Callsigns" (HTML). United States Early Radio History. http://www.earlyradiohistory.us/3myst.htm#dawn. Retrieved January 10, 2010. "A ship station was not as fortunate. KGOV was assigned to the Morro Castle, which went on to burn spectacularly off the New Jersey coast in 1934. However, surprisingly KGOV is currently unavailable for use by broadcasting stations, since it is technically still assigned to the ship, according to the FCC's online Callsign Query page."

- ↑ Webster, Charles (September 8, 2009), "Monument unveiled in Asbury Park to Morro Castle victims", Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, NJ: Gannett Co.), OCLC 16894042, http://www.app.com/article/20090908/NEWS/90908177/1282/LOCAL06/Monument+unveiled+in+Asbury+Park+to+Morro+Castle+victims, retrieved January 10, 2010

Further reading

- Thomas, Gordon; Witts, Max Morgan (1972), Shipwreck: The strange fate of the Morro Castle, New York: Stein and Day, ISBN 9780812814385, OCLC 447229

- Hicks, Brian (2006). When the Dancing Stopped: The Real Story of the Morro Castle Disaster and its Deadly Wake

- Gallagher, Thomas (1959), Fire at Sea: The Story of the 'Morrow Castle', New York: Rinehart & Company, OCLC 1227134

External links

- The Ward Line's Ill-Fated Morro Castle

- The Morro Castle, the Mohawk and the End of the Ward Line (Ilustrated article)

- A Morro Castle Survivor's Story in his own words by George Watremez

- Description of the ship

- Photo of the ship

- The Boardwalk in Asbury Park. more photos and stories.

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2010

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Pages with broken file links

- United States articles missing geocoordinate data

- All articles needing coordinates

- Ships of the Ward Line

- Steamships

- Shipwrecks of the New Jersey coast

- Ship fires

- Maritime incidents in 1934

- 1930 ships