SS Normandie

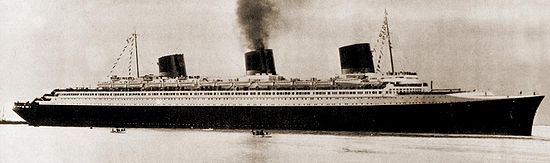

| 300px SS Normandie at sea in the 1930s | |

| Career (France) | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SS Normandie |

| Owner: | Compagnie Générale Transatlantique |

| Builder: | Penhoët, Saint Nazaire, France |

| Laid down: | 26 January 1931 |

| Launched: | 29 October 1932 |

| Christened: | 29 October 1932 |

| Maiden voyage: | 29 May 1935 |

| Fate: | Caught fire, capsized 1942. Sold for scrap October 1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 79,280/83,423 gross tons |

| Displacement: | 71,300 tons (approx) |

| Length: | 1,029 feet (314 m) |

| Beam: | 119.4 feet (36.4 m) |

| Height: | 184 feet (56 m) |

| Draft: | 37 feet (11 m) |

| Decks: | 12 |

| Installed power: | Four turbo-electric, total 160,000 hp (200,000 hp max). |

| Propulsion: | Four 3- (later 4-) bladed, 23 tons each |

| Speed: | Designed speed 29 knots (54 km/h), max speed recorded 32.2 knots (59.6 km/h) |

| Capacity: | 1,972: 848 First Class (cabin), 670 Tourist Class, 454 Third Class |

| Crew: | 1,345 |

SS Normandie was an ocean liner built in Saint-Nazaire, France for the French Line Compagnie Générale Transatlantique. She entered service in 1935 as the largest and fastest passenger ship afloat; she is still the most powerful steam turbo-electric-propelled passenger ship ever built.[1][2]

Her novel design and lavish interiors led many to consider her the greatest of ocean liners.[3][4] Despite this, she was not a commercial success and relied partly on government subsidy to operate.[4] During service as the flagship of the CGT, she made 139 transatlantic crossings westbound from her home port of Le Havre to New York and one fewer return. Normandie held the Blue Riband for the fastest transatlantic crossing at several points during her service career, during which the RMS Queen Mary was her chief rival.

During World War II, Normandie was seized by the United States authorities at New York and renamed USS Lafayette. In 1942, the liner caught fire while being converted to a troopship, capsized and sank at the New York Passenger Ship Terminal. Although salvaged at great expense, restoration was deemed too costly and she was scrapped in October 1946.[5]

Contents

Origin

The beginnings of Normandie can be traced to the Roaring Twenties when shipping companies began looking to replace veterans such as the RMS Mauretania which had first sailed in 1907.[6] Those earlier ships had been designed around the huge numbers of steerage-class immigrants from Europe to the United States. When the U.S. closed the door on most immigration in the early 1920s, steamship companies ordered vessels built to serve upper-class tourists instead, particularly Americans who traveled to Europe for alcohol-fueled fun during Prohibition.[4] Companies like Cunard and the White Star Line planned to build their own superliners[7] to rival newer ships on the scene; such vessels included the record-breaking Bremen and Europa, both German.[4] The French Line began to plan its own superliner.[6]

The French Line's flagship was the Ile de France,[6] which had modern Art Deco interiors but conservative hull design. The designers of the new French superliner intended to construct their new ship similar to French Line ships of the past[6] but then they were approached by Vladimir Yourkevitch, a former ship architect for the Imperial Russian Navy, who had emigrated to France before the revolution. His ideas included a slanting clipper-like bow and a bulbous forefoot beneath the waterline, in combination with a slim hull. Yourkevitch's concepts worked wonderfully in scale models[8][9] which supported his design's performance advantages. The French engineers were impressed and asked Yourkevitch to join their project. Reportedly, he also approached the Cunard Line with his ideas but was rejected because the bow was deemed too radical.[4]

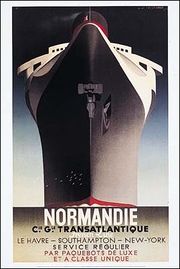

The French Line commissioned artists to create posters and publicity for the liner. One of the most famous posters was by Adolphe Mouron Cassandre,[10] who was also a Russian emigrant to France. Another cutaway diagram by Albert Sébille, 15 feet long, detailed the interior layout and is displayed in the Musée national de la Marine in Paris.[11]

Construction and launch

Work began on the unnamed flagship in January 1931, soon after the stock market crash of 1929. While the French continued construction, the competing White Star Line's ship (intended as Oceanic) – started before the crash – was cancelled and the Cunard ship put on hold.[7] French builders also ran into difficulty and had to ask for government money; this subsidy was questioned in the press. Still, building was followed by newspapers and national interest was deep, as she was designed to represent France in the nation-state contest of the great liners and was built in a French shipyard using French parts[12] .

The growing hull in Saint-Nazaire had no formal designation except "T-6" (with "6" for "6th" and "T" for "Transat", short for "CIE. GLE. TRANSATLANTIQUE" aka the "French Line"), the contract name. Many names were suggested including Doumer, after the recently assassinated president Paul Doumer, and originally, La Belle France.[13] Finally Normandie was chosen. In France, ship prefixes are customarily masculine,[13] inherited from the French terms for ship, which can be "paquebot", "navire", "bateau", "bâtiment", but English speakers refer to ships as feminine ("she's a beauty"), and the French Line carried many rich American customers. French Line wrote that their ship was to be called simply "Normandie," preceded by neither "le" nor "la" (French masculine/feminine for "the") to avoid any confusion.[9]

On 29 October 1932 – three years to the day after the stock market crash – Normandie was launched in front of 200,000 spectators.[14] The 27,567 ton hull that slid into the Loire River was the largest launched and the wave crashed into a few hundred people, but with no injury.[15] Normandie was outfitted until early 1935, her interiors, funnels, engines, and other fittings put in to make her into a working vessel. Finally, in May 1935, Normandie was ready for trials, which were watched by reporters.[16] The superiority of Vladimir Yourkevitch's hull was visible: hardly a wave was created off the bulbous bow. The ship reached a top speed of 32.125 knots (59.496 km/h)[17] and performed an emergency stop from that speed in 1,700 meters.

In addition to a novel hull which let her attain her speed at far less power than other big liners,[18] Normandie was filled with technical feats. She had turbo-electric engines, chosen for their ability to allow full reverse power,[2] and, according to French Line officials, which were quieter and more easily controlled and maintained.[2] The engine installation was heavier than conventional turbines and slightly less efficient at high speed but allowed all propellers to operate even if one engine was not running. This system also made it possible to do away with astern turbines.[2] An early form of radar was installed.[19]

Interior

The luxurious interiors were designed in Art Déco and Streamline Moderne style. Many sculptures and wall paintings made allusions to Normandy, the province of France for which Normandie was named.[20] Drawings and photographs show a series of vast public rooms of great elegance. Normandie's voluminous interior spaces were made possible by having the funnel intakes split to pass along the sides of the ship, rather than straight upward.[14]

Most of the public space was devoted to first-class passengers, including the dining room, first-class lounge, grille room, first class swimming pool, theatre and winter garden. The first class swimming pool featured staggered depths, with a shallow training beach for children.[21] The children's dining room was decorated by Jean de Brunhoff, who covered the walls with Babar the Elephant and his entourage.[22][23]

The interiors were filled with grand perspectives, spectacular entryways, and long, wide staircases. First-class suites were given unique designs by select designers. The most luxurious accommodations were the Deauville and Trouville apartments,[24] featuring dining rooms, baby grand pianos, multiple bedrooms, and private decks.[21]

The first class dining hall was the largest room afloat. At three hundred and five feet (93 m) it was longer than the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles,[25][26] stood 46 feet (14 m) wide, and towered 28 feet (8.5 m) high. Passengers entered through 20-foot (6.1 m) tall doors adorned with bronze medallions by artist Raymond Subes.[27] The room could seat 700 at 157 tables,[25] with Normandie serving as a floating promotion for the most sophisticated French cuisine of the period. As no natural light could enter [25] it was illuminated by 12 tall pillars of Lalique glass flanked by 38 matching columns along the walls.[25] These, with chandeliers hung at each end of the room, earned the Normandie the nickname "Ship of Light"[21] (similar to Paris as the '"City of Light").

A popular feature was the café grill, which would be transformed into a nightclub.[28] Adjoining the cafe grill was the first class smoking room, which was paneled in large murals depicting ancient Egyptian life. Normandie also had indoor and outdoor pools, a chapel, and a theatre which could double as a stage and cinema.[29][26]

The machinery of the top deck and forecastle was integrated within the ship, concealing it and releasing nearly all the exposed deck space for passengers. The air conditioner units were concealed along with the kennels inside the third, dummy, funnel.[30]

Career

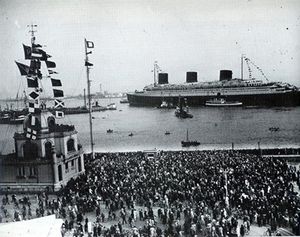

Normandie's maiden voyage was on 29 May 1935. Fifty thousand saw her off at Le Havre on what was hoped would be a record-breaking crossing. Normandie reached New York after four days, three hours and 14 minutes, taking way the Blue Riband from the Italian liner, Rex.[31] This brought great pride for the French, who had not won the distinction before. Under the command of master, Captain René Pugnet, her average on the maiden voyage was around 30 knots (56 km/h) and on the eastbound crossing to France she averaged over 30 knots (56 km/h), breaking records .[32]

During the maiden voyage, French Line refused to predict that their ship would win the Blue Riband.[4] However, by New York, medallions of the Blue Riband victory, made in France, were delivered to passengers and the ship was flying a 30-foot (9.1 m) long blue pennant.[4][31] An estimated 100,000 spectators lined New York Harbor for Normandie's arrival.[33]

Normandie had a successful year but RMS Queen Mary, Cunard's superliner, entered service in the summer of 1936. Cunard said the Queen Mary would surpass 80,000 tons.[34] At 79,280 tons, Normandie would no longer be the world’s largest. French Line increased Normandie’s size, mainly through the addition of an enclosed tourist lounge on the aft boat deck. Following these and other alterations, Normandie was 83,423 gross tons.[34] Exceeding the Queen Mary by 2,000 tons, she would remain the world’s largest in terms of overall measured gross tonnage.[34] However in August that year, Queen Mary captured the Blue Riband, averaging 30.14 knots (55.82 km/h), starting fierce rivalry.[4] The Normandie held the size record until the arrival of RMS Queen Elizabeth (83,673 gross tons) in 1940.[35]

During refit, Normandie was also modified to address vibration. Her triple-bladed screws were replaced with quadruple-bladed ones, and structural modifications were made to her lower aft section. These modifications reduced vibration at speed.[36][37]

In July 1937 Normandie regained the Blue Riband, but the Queen Mary took it back next year. After this the captain of Normandie sent a message saying "Bravo to the Queen Mary until next time!" This rivalry could have gone on into the 1940s but was ended by World War II.

Normandie carried distinguished passengers, including the authors Colette and Ernest Hemingway,[38] the wife of French President Albert Lebrun,[31] songwriters Noël Coward and Irving Berlin, and Hollywood celebrities such as Fred Astaire, Marlene Dietrich, Walt Disney, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr, and James Stewart.[39] Normandie also carried the von Trapp family Singers of The Sound of Music from New York to Southampton in 1938, and from Southampton, the family went to Scandinavia for a tour before returning to America.

French Line considered a sister ship, the SS Bretagne, which was to be longer and larger, but war and limited finances prevented it.[40]

Popularity

Although a success in her design and decour, the Normandie ultimately proved to be unpopular with North Atlantic passengers. Two of the ships greatest attributes, in reality, turned out to be two of her biggest detractors.

Part of the ship's problem lay in the fact that the majority of her passenger space was devoted solely to first class, which could carry up to 848 people. Less space and consideration were given to second and tourist class, which only numbered 670 and 454 passengers respectfully. As a result the general consensus amongst North Atlantic passengers was that she was primarily a ship for rich and the famous. In contrast Cunard had placed just as much emphasis on decor, space, an accomodations in second and tourist class on the Queen Mary as it had with first, thus accomodating a travel trend that had become popular during the 20's and the 30's, the American tourist. Many of these passengers could not afford first class passage yet wanted to travel with much of the same comfort as those in first. Thus second and tourist class became a major cash cow for shipping companies at that time. The Mary would accommodate this and thus she had great popularity among North Atlantic travelers in the late thirties. </ref>http://www.thegreatoceanliners.com/normandie.html

Another of the French Liner's greatest triumphs also turned out to be one of her greatest flaws: her decor. The Normandie's slick and modern art deco interiors proved to be somewhat intimidating and uncomfortable for her travelers. It was also here that Queen Mary triumphed over her French rival. Although decorated in an art deco style, the Queen Mary was more reserved in her appointments and was not as radical as her French counterpart, which ultimately proved to be popular with her passengers.</ref>http://www.thegreatoceanliners.com/normandie.html

As a result throughout her service history the Normandie rarely topped more than sixty percent occupancy, and at many times travelled with less than half a compliment of passengers. Her German rivals the Bremen, and the Europa, and Italian rivals the Rex, and Conte de Savioa also suffered from this problem; despite their innovative designs and luxurious interiors, they never made a dime for their respective companies, relying on heavy government subsidies. In contrast the Queen Mary, and Cunard's Mauretania II, and much older Aquitania, along with the Holland America Line's SS Nieuw Amsterdam were amongst the few ships on the North Atlantic to make a profit, holding the lion's share of North Atlantic passengers in the years preceding the Second World War.</ref>http://www.thegreatoceanliners.com/normandie.html

Demise

The war found Normandie in New York. Soon the Queen Mary, later refitted as a troop ship, docked nearby. Then the RMS Queen Elizabeth joined the Queen Mary. For two weeks the three largest liners in the world floated side by side.[41] In 1940, after the Fall of France, the United States seized the Normandie under the right of angary. By 1941, the U.S. Navy decided to convert Normandie into a troopship, and renamed her USS Lafayette (AP-53), in honor both of Marquis de la Fayette the French general who fought on the Colonies' behalf in the American Revolution and the alliance with France that made American independence possible.

Earlier proposals included turning the vessel into an aircraft carrier, but this was dropped in favor of immediate troop transport.[42] The ship was moored at Manhattan's Pier 88 for the conversion. On February 9, 1942, sparks from a welding torch ignited a stack of thousands of life vests filled with kapok, a highly flammable material, that had been stored in the first-class dining room.[43][44] The woodwork had not yet been removed, and the fire spread rapidly. The ship had a very efficient fire protection system but it had been disconnected during the conversion and its internal pumping system was deactivated.[45] The New York City fire department's hoses also did not fit the ship's French inlets. All on board fled the vessel.

As firefighters on shore and in fire boats poured water on the blaze, the ship developed a dangerous list to port due to water pumped into the seaward side by fireboats. About 2:45am on February 10, Lafayette capsized, nearly crushing a fire boat.

The ship's designer Vladimir Yourkevitch arrived at the scene and offered expertise, but he was barred by harbor police.[38][46] His suggestion was to enter the vessel and open the sea-cocks. This would flood the lower decks and make her settle the few feet to the bottom. With the ship stabilised, water could be pumped into burning areas without the risk of capsize. However, the suggestion was denied by port director Admiral Adolphus Andrews.

The ship was stripped of superstructure and righted in 1943 in the world's most expensive salvage operation. The cost of restoring her was subsequently determined to be too great. After neither the US Navy nor French Line offered, Yourkevitch proposed to cut the ship down and restore her as a mid-sized liner.[47] This failed to draw backing and the hulk was sold for $161,680 to Lipsett Inc., an American salvage company. She was scrapped on October 1946.[5]

Legacy

Designer Marin-Marie gave an innovative line to Normandie, a silhouette which influenced ocean liners over the decades, including the Queen Mary 2. The design of Normandie and her chief rival, the Queen Mary, was the main inspiration for Disney Cruise Line's matching vessels, the Disney Magic and Disney Wonder.[48]

The SS Normandie also inspired the architecture and design of the Normandie Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Items from Normandie were sold at a series of auctions after her demise,[49] and many pieces are considered valuable Art Deco treasures today.

The rescued items include the ten large dining room door medallions and fittings, and some of the individual Jean Dupas glass panels that formed the large murals mounted at the four corners of her Grand Salon.[49] Also surviving are some examples of the 24,000 pieces of crystal, some from the massive Lalique torchères, that adorned her Dining Salon. Also some of the room's table silverware, chairs, and gold-plated bronze table bases. Custom-designed suite and cabin furniture as well as original artwork and statues that decorated the ship, or were built for use by the French Line aboard Normandie, also survive today.[49] Pieces from the Normandie occasionally appear on the BBC TV series Antiques Roadshow.[citation needed] A public lounge and promenade was created from some of the panels and furniture from the SS Normandie in the Hilton Chicago.

Profile views

See also

- SS Paris (1916)

- SS Ile de France

- SS Liberté

- SS France (1961)

- Compagnie Générale Transatlantique

- RMS Queen Mary

- RMS Queen Elizabeth

References

- ↑ "Colossus into Clyde". TIME. 1934-10-01. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,930557-2,00.html. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ardman, Harvey. "Normandie, Her Life and Times," New York, Franklin Watts, 1985. p. 46-47

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Floating Palaces. (1996) A&E. TV Documentary. Narrated by Fritz Weaver

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Maxtone-Graham, John. The Only Way to Cross. New York: Collier Books, 1972, p. 391

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Ardman 1985, p. 36

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 268-69

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 42-47

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 273

- ↑ Reif, Rita (1988-06-26). "Antiques - A Proliferation Of Poster Art". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940DE5D91E3EF935A15755C0A96E948260. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 267.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 269-272

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 272

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 275

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 7, 17-20

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 281

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 111

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 171

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 160

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 80

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Maddocks, Melvin The Great Liners. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1978, p.80-83

- ↑ Cech, John (2004-10-12). "Jean de Brunhof and Babar the Elephant". http://www.recess.ufl.edu/transcripts/2004/1210.shtml. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 372

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 279

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Ardman 1985, p. 86-87

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 276

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 85-86

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 88>

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 91-92

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 273-75

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 284

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 147

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 137

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Ardman 1985, p. 166-170

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 221

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 172-73

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 286-87

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Ardman 1985, p. 325-26

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 147, 184-85, 205, 218, 238

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 237, 423

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 360-61

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 274-276

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 299

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 367-68

- ↑ Ardman 1985, p. 272, 304-14

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 373-74

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 392

- ↑ "Imagination Creates Atmosphere On Disney Wonder, UK". British Design Innovation. 2003-05-27. http://www.britishdesigninnovation.org/index.php?page=newsservice/view&news_id=2431. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Ardman 1985, p. 418-20

Further reading

- Ardman, Harvey. "Normandie, Her Life and Times," New York, Franklin Watts, 1985

- Brinnin, John Malcolm. The Sway of the Grand Saloon : a Social History of the North Atlantic. New York : Delacorte Press, 1971

- Coleman, Terry. The liners : a history of the North Atlantic crossing. Harmondsworth, England : Penguin Books, 1977

- Fox, Robert. Liners: The Golden Age. Die Grosse Zeit der Ozeanriesen. L'Âge d'or des paquebots. [trilingual text] Cologne: Konneman, 1999.

- Kludas, Arnold. Record breakers of the North Atlantic - Blue Riband Liners 1838-1952, Chatham Publishing, London, 2000.

- Maddocks, Melvin The Great Liners. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1978.

- Maxtone-Graham, John. The Only Way to Cross. New York: Collier Books, 1972.

- Boks, W. Holland: photo of the model boat SS Normandie 1935.

- Lange Eric & Villers Claude (directed by, original footages by Jean Vivié) A Bord Du Normandie (on board Normandy). Produced by Lobster. France 2005.

- Streater, L. 5 volume series of books from construction to salvage, Marpubs, 2007

External links

| SS Normandie

]]- Smoke Over Manhattan: The Fate of the SS Normandie

- SS Normandie – Magnificent Voyage - Miottel Collection

- Normandie: A Photographic Portrait

- The Normandie - A Dream of Giant

- The Normandie - virtual reality tour of the Art Deco masterpiece

- SS Normandie - photos and details of books

- French Lines Archives - the liner Normandie

- Pictures in the official French Lines Archives : SS Normandie (French captions)

- The Great Ocean Liners: Normandie

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Rex |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound) 1935 – 1936 |

Succeeded by Queen Mary |

| Preceded by Bremen |

Atlantic Eastbound Record 1935 – 1936 | |

| Preceded by Queen Mary |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound) 1937 – 1938 | |

| Atlantic Eastbound Record 1937 – 1938 | ||

da:SS Normandie de:Normandie (Schiff) es:SS Normandie fr:Normandie (paquebot) hr:Normandie it:Normandie (transatlantico) hu:SS Normandie nl:Normandie (schip) ja:ノルマンディー (客船) no:SS «Normandie» pl:SS Normandie ru:Нормандия (лайнер) fi:S/S Normandie

- Pages with broken file links

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2009

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Ocean liners

- Art Deco ships

- Ships built in France

- Blue Riband holders

- Passenger ships of France

- Ship fires

- Shipwrecks of the New York coast

- Maritime incidents in 1942

- 1932 ships