Proa

A proa, prau or perahu (also seen as prahu) is a type of multihull sailing vessel.

While the word perahu and proa are generic terms meaning boat their native language. Proa in Western languages has come to describe a vessel consisting of two (usually) unequal length parallel hulls. It is sailed so that one hull is kept to windward, and the other to leeward, so that it needs "shunt" or to reverse direction when tacking. The English term proa most likely specifically refers the South Pacific proa as detailed by the analysis a Micronesian proa by the British ship The Centurion..

The perahu traditional outrigger boat is most numerous in the various islands of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines. These differ from the South Pacific vessels. Traditional proas superficially resemble outrigger canoes, with a buoyant lee hull and a denser, ballasted hull to windward for stability.

To Americans, the boats of the Marianas Islands and Marianas Islands are arguably the most recognizable version.

The modern proa exists in a wide variety of forms, from the traditional archetype still common in areas described, to high-technology interpretations specifically designed for breaking speed-sailing records.

Contents

Etymology

The word proa comes from perahu, the word for "boat" in Indonesian (paraw in similar Borneo-Philippine languages), which are similar to the Micronesian language group.[1] Found in many configurations and forms, the proa was likely developed as a sailing vessel in Micronesia (Pacific Ocean). Variations may be found as distant as Madagascar and Sri Lanka, as far back as the first century. Such vessels go by many names, and "perahu" is a generic umbrella term for any boat smaller than a ship.

The so-called "proa" was documented by the Spanish Magellan expedition to the Philippines circa 1519 CE. It entered English lexicography later. The use of the term proa in English with reference to the Micronesian craft dates back to at least 1742 (see below).

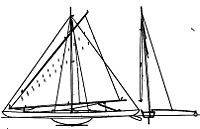

The first illustrations to known to Europeans appeared around the middle 1800's CE in Europe, ushering in a period of interest in the design. Western builders, working from the drawings and descriptions of explorers: often took liberties with the traditional designs; merging their interpretation of native designs with Western boatbuilding methods. Thus this Western "proa" often diverged radically from the traditional "proa" to the point the only shared feature was the windward/leeward hull arrangement.

Various native names of the various components of the proa have also entered the jargon of sailing. The main hull of the proa is known as the vaka, the outrigger as the ama, and the outrigger supports as the akas. The terms vaka, ama, and aka have been adopted in Western sailing to describe the analogous parts in trimarans.

Proa characteristics

The defining feature of the proa is that the vessel "shunts" when it changes tacks: the stern becomes the bow and vice versa. The same hull is kept windward for ballast.

The main hull, or vaka, is usually longer than the windward hull, or ama. Crossbeams called akas connect the vaka to the ama. Traditional proa hulls are markedly asymmetrical along their length, and often curved in such a way as to produce lift to counteract the lateral forces of the wind. Modern proa hulls are often symmetrical, and use leeboards for lateral resistance.

There are a number of other vessels that use a similar layout, with uneven hulls and a shunting sails, but are culturally and historically distinct from the Western interpreted-invented proa. Examples of these are the Fijian drua and the Melanesian tepukei.

Size and sail plan

The Micronesian proa is found in a variety of sizes, from the small, canoe-like kor-kor (about 15 feet (4.6 m) in length) to the medium-sized tipnol (20 to 30 feet (6.1 to 9.1 m)), to the tremendous walap, which can be up to 100 feet (30 m) long.

There is also a model proa, called a riwuit, that is often raced by children. Proas could be paddled or sailed. The traditional sail used on the proa was the crab-claw sail. The crab-claw sail generates far more lift than the more common triangular sloop rig used on small boats, particularly when reaching. The sloop rig only begins to show an advantage with small angles of attack, such as encountered when close-hauled. This is the result of the higher aspect ratio of the sloop.

The crab-claw sail is something of an enigma. It has been demonstrated to produce very large amounts of lift when reaching, and overall seems superior to any other simple sail plan (this discounts the use of specialized sails such as spinnakers). C. A. Marchaj, a researcher who has experimented extensively with both modern rigs for racing sailboats and traditional sailing rigs from around the world, has done wind tunnel testing of scale models of crab-claw rigs. One popular but disputed theory is that the crab-claw wing works like a delta wing, generating vortex lift. Since the crab claw does not lie symmetric to the airflow, like an aircraft delta wing, but rather lies with the lower spar nearly parallel to the water, the airflow is not symmetric.

This can clearly be seen in Marchaj's wind tunnel photos published in Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximize Sail Power (ISBN 0-07-141310-3). The vortex on the top spar of the sail is much larger, covering most of the sail area, while the lower vortex is very small and stays close to the spar. Marchaj attributes the large lifting power of the sail to lift generated by the vortices, while others attribute the power to a favourable mix of aspect ratio, camber and (lack of) twist at this point of sail.[2]

Sailing the proa

When sailing in a strong wind, the crew of the proa act as ballast, providing a force to counteract the torque of the wind acting on the sail. The weight of the crew can provide considerable torque as they move out along the akas towards the ama. A skilled crew will balance the proa so that the ama leaves the water and skims over its surface; this is called "flying the ama", and gives the proa its nickname, the "flying proa". By flying the ama, the wetted surface, and therefore the drag of the proa is significantly reduced. When combined with the long, narrow shape of the vaka, and the large amount of torque the crew can apply on the akas, this gives the proa its great potential speed.

Historical descriptions of the proa

- The Proa darted like a shooting star

- Lord Byron, "The Island", 1823

Vessels that have a bow at either end are found scattered throughout history, with the earliest mention being in Pliny the Elder's Natural History. He describes double-ended vessels being used to transport cargo across the strait at Taprobane, or what is now the Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka, where the double-ended nature of the vessels allowed them to ferry cargo back and forth without turning around.[3]

The written history of the Micronesian proa began when it was recorded after encounter by European explorers in the Micronesian islands. The earliest written accounts were by Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian who was a passenger on Ferdinand Magellan's 1519—1522 circumnavigation. Pigafetta's account of the stop at approximately 146 E, 12 N, (the Mariana Islands, named the Ladrones by Magellan's men), describes the proa's outrigger layout, and ability to switch bow for stern, and also notes the proa's speed and maneuverability, noting, "And although the ships were under full sail, they passed between them and the small boats (fastened astern), very adroitly in those small boats of theirs." Pigafetta likened the proa to the Venetian fisolere, a narrow variety of gondola; this was an apt comparison due to both the long, thin shape and asymmetric nature of single-oar gondolas.[4][5][6]

During his 1740—1744 circumnavigation, Lord Anson also saw the proa. His fleet captured one in 1742, and Lt. Peircy Brett of the HMS Centurion made a detailed sketch of the proa.[7] Rev. Richard Walter, chaplain of the HMS Centurion, estimated the speed of the proa at twenty miles per hour (32 km/h).[8] Since Pigafetta's account was not fully published until the late 18th century (though finished in 1525), the accounts from Anson's voyage were the first about the proa for most literate Europeans.[9]

Construction

Scholars believe the proa evolved from the dugout canoe, one of the oldest watercraft and found in primitive cultures across the world. The design of the proa hints at its evolution from a canoe into the world's fastest sailboat. It likely held this position for many centuries.

Vaka (main hull)

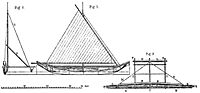

The traditional Micronesian proa hull consists of a single long keel made of a single large log constructed much like a dugout canoe. It is extended upwards with sewn planks, to provide additional depth to the hull. The windward side of the hull is curved, similar to a typical canoe, while the lee side is straight and flat to minimize leeway while sailing.[8]

Ama (outrigger)

Adding a sail to a narrow hull like a canoe is a dangerous proposition, especially given the lack of dense materials like lead that can be used in a ballasted keel to counter the heeling moment of the sail. Attaching two dugout canoes together to form a catamaran hull provides stability, but this is an expensive operation. For men using nothing but fire and stone tools, building a hull is a long and labor-intensive process. The traditional proa's simple outrigger—a log hewn to a point at each end—can be produced with far less effort, and provides the needed stability to counter the force of a large sail.

Rigging

The rigging of the proa also shows a high degree of elegance. By keeping the wind always to one side of the boat, the forces act on the sail, mast, rigging and akas always in the same direction. Where a tacking boat must have stays on both sides of the mast, with only one set under tension at a time, the layout of the proa requires stays on only one side, where they are under tension on all points of sail. Having the ama to the windward side also allows the use of materials like bamboo for the akas—the akas only need to be able to bear the weight of the ama, which is countered by the tension on the stays. Leeward akas, on the other hand, would need to bear the displacement of the ama, and cannot be assisted by tensioned rope.

Modern variations

In the Marshall Islands, where the craft were traditionally built, there has been a resurgence of interest in the proa. People hold annual kor-kor races in the lagoon at Majuro, along with events such as a children's riwut race. The kor-kors are built in traditional style out of traditional materials, though the sails are made with modern materials (often inexpensive polyethylene tarpaulins, commonly known as polytarp).

A loose group of individuals from all over the world has formed from those interested in the proa, including people with a historical perspective and those with a scientific and engineering perspective. Many such individuals are members of the Amateur Yacht Research Society.

Early Western proas

- Sailing is no name for it - flying is better. Out into the bay she skipped, boys yelling with delight on the uplifted outrigger, spray from the lee bow and steering oar riven into vapor by the speed blowing to leeward.

- R. M. Munroe, "A Flying Proa", The Rudder, June 1898

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many in Europe and America became interested in the proa. Western boat builders such as R. M. Munroe and Robert Barnwell Roosevelt (Theodore Roosevelt's uncle) reflected its influence. Into the 20th century, the proa was one of the fastest sailing craft that existed. The proa design is still the basis for many boats involved in speed sailing.

The first well-documented Western version of the proa was built in 1898 by Commodore Ralph M. Munroe of the Biscayne Bay Yacht Club. Yacht-design giant Nathanael Herreshoff, a friend of Munroe, may have also had an interest in the project. A small model of the Anson-Brett proa is collected at the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Rhode Island; its maker is uncertain.

Over the following years, Munroe built several more. They were all destroyed by the mid-1930s, when a severe hurricane leveled Munroe's bayside boatshop. At least two of his designs were documented in articles in The Rudder, as was one by Robert B. Roosevelt. Small proas may have been brought back to the United States in the late 1800s, but documentation is sparse. Munroe and Roosevelt appeared to be the first two builders to adapt the proa to Western building techniques.

Royal Mersey Yacht Club

In 1860 a member of the Royal Mersey Yacht Club in England built a copy of a Micronesian proa. He used the traditional asymmetric hull, flat on the lee side, and a decked dugout ama. While no quantitative record was made of its speed, it was noted that the proa would run at speeds that would bury the bows of any other vessel. It carried three times the ratio of sail area to immersed midships section than the fastest yachts in the club and yet drew only 15 inches (38 cm).[8]

Munroe's 1898 proa

Since Munroe had no direct experience with proas, all he had to work with was the widely distributed and incorrect plan drawing from about 1742, made during Admiral Lord Anson's circumnavigation of the globe. This drawing had been circulated in the press, for example in William Alden's articles in Harper's Magazine. (These were reprinted in a small book called The Canoe and the Flying Proa. This proa was one of several either captured or seen under sail when Anson stopped at Tinian during a Pacific crossing. Brett, the draftsman of the plan, misinterpreted one key element, showing it fixed vertically in the center of the boat. Traditional proa masts were raked end-to-end as the vessel shunted. A raking mast helps with helm balance by moving the center of effort of the sail fore and aft.

Munroe, however, was a talented boat designer who was able to work around the problems with the drawings. His adaptations can be seen in successive proas. Rather than the deep, asymmetric hull of a traditional proa, Munroe created flat-bottomed hulls (similar to the fisolera referred to by Pigafetta[5]), with keels or centerboards for lateral resistance. His first iteration had an iron center fin with a half-oval profile. Rather than the traditional crab-claw sail's spars which meet at the front, Munroe's sails used what could be described as a triangular lugsail or spritsail with a boom, similar to the modern lateen sail with a shorter upper spar.

Munroe's first proa was only 30 feet (9.1 m) long, yet was capable of speeds which Munroe estimated at 18 knots (33 km/h). His article in The Rudder describes what can only be planing on the flat hull. As this was before the advent of planing power boats, this proa was one of the first boats capable of planing. This helped produce its amazing speed when most boats were limited by hull speed. For example, a 30-foot boat that was not capable of planing would have a hull speed of about 7.3 knots (13.5 km/h); Munroe's proa could reach nearly 2.5 times that speed. This accomplishment was the nautical equivalent to the X-1 breaking the sound barrier.

It is not clear that traditional proas of the Pacific islanders could plane, though the long, slender hull would have a much higher speed/length ratio than other contemporary designs. Munroe was building a "cheap and dirty" sharpie hull made of two 32-foot planks, a couple of bulkheads and a crossplanked bottom. By lucky accident he may have been the first sailor to plane his boat.[10]

Roosevelt's Mary & Lamb

Robert Barnwell Roosevelt, uncle of American President Theodore Roosevelt, also built a proa at about the same time. He used it sailing from Long Island. It was significantly different but equally creative, and at 50 feet (15 m), much longer. From his 1898 article in The Rudder, it appeared the main hull of Roosevelt's proa was an open 4-foot (1.2 m) wide scow hull; the ama was a smaller, fully decked scow which looked like it could rock on a single aka. The mast was a bipod arrangement with both masts stepped to windward, with a boomed, balanced lugsail suspended from the apex. A balanced rudder at each end managed itself by pivoting 180° when its end was the "bow", and leeboards were used.

Roosevelt's short article is accompanied by photographs showing his proa Mary & Lamb, at rest and under sail. It is not clear if the boat predated Munroe's 1898 proa.

Munroe's 1900 Proa

Since Munroe wasn't aware of the raking mast, his 1900 model used two daggerboards set fore and aft of the mast, which would allow adjustment of the center of lateral resistance to provide helm balance. From the drawings, it appears the mast is higher as well, allowing a larger sail. The sail design also changed, with the upper spar now being slightly longer than the upper edge of the sail, and projecting past the apex slightly to allow the apex to be attached to the hull. The sail was loose footed, with the boom attached to the upper spar near the sail apex, and to the clew of the sail. His article in a 1900 issue of The Rudder included more details on the construction of his second proa. A 1948 book of sailboat plans published by The Rudder includes the following specifications for the 1900 proa:

- Length overall 30 feet (9.1 m)

- Beam (of main hull) 2 feet 6 inches (0.76 m)

- Draft of hull about 5 inches (13 cm)

- Draft with boards down 2 feet 5 inches (0.74 m)

- Sail area 240 square feet (22 m2)

From the drawings, the distance from the center of the main hull to the center of the aka is about 12 feet (3.7 m).

Other Western Interpretations

Western designers often feel the need to tinker with the proa. They are attracted by the minimalist nature and amazing speeds that proas are capable of (they may still be the fastest sailboats per dollar spent for the home builder) but they often want the proa to do more; adding cabins, different sailing rigs, and bidirectional rudders are common changes made.

For example, unconventional boat and yacht designer Phil Bolger has drawn at least three proa designs; the smallest one (20 ft) has been built by several people while the larger two, including his Proa 60, have not been built. For additional examples, see here.

Lee pods

The terms ama and aka have been adopted for the modern trimaran. Since trimarans are generally designed to sail with one ama out of the water, they are similar to an Atlantic proa, with the buoyant leeward ama providing the bulk of the stability for the long, relatively thin main hull. Some modern proa designers have borrowed trimaran design elements for use in proas. Trimarans often have main hulls that are very narrow at the waterline, and flare out and extend over a significant portion of the akas. This topheavy design is only practical in a multihull, and it has been adapted by some proa designers. Notable examples are the designs of Russell Brown, a boat-fittings maker who designed and built his first proa, Jzero, in the mid 1970s. He has created a number of proa designs, all of which follow the same theme.

One of the design elements which Brown used, and a number of other designers have copied, is the lee pod. The akas extend past the main hull and out to the lee side, and provide support for a cabin extending to the lee of the main hull. This is similar to the platform extending to the lee on some Micronesian proas. The lee pod serves two purposes—it can be used for bunk space or storage, and it provides additional buoyancy on the lee side to prevent a capsize should the boat heel too far. Crew can also be moved onto the lee pod to provide additional heeling force in light winds, allowing the ama to lift under circumstances when it would not otherwise. The Jzero also used water ballast in the ama to allow the righting moment to be significantly increased if needed. While Brown's proa was designed to be a cruising yacht, not a speed-sailing boat, the newer 36-foot Jzerro is capable of speeds of up to 21 knots (39 km/h).

Sail rigs

One of the issues Western designers have with the proa is the need to manipulate the sail when shunting. Even Munroe's early sails discarded the curved yards of the traditional crabclaw for the more familiar straight yards of the lateen and lug sails. Munroe's designs likely lacked the tilting mast because he was unaware of it, but many designers since have use a fixed mast, and provided some other way of adjusting the center of effort. Most sailboats are designed with the center of effort of the sails slightly ahead of the center of area of the underwater plane; this difference is called "lead." In a proa hull, and in all fore and aft symmetric foils, the center of resistance is not at or even near the center of the boat, it is well forward of the geometric center of area. Thus the center of effort of the sails needs to also be well forward, or at least needs to have a sail which is well forward which can be sheeted in to start the boat moving, allowing the rudders to bite and keep the boat from heading up when the entire sail area is sheeted in. Jzero, for example, and all of Russell Brown's other designs, use a sloop rig and hoist a jib on whichever end is the current "bow". Other designs use a schooner rig for the same effect.

One of the more practical rigs for small proas was invented by Euell Gibbons around 1950 for a small, single handed proa. This rig was a loose footed lateen sail hung from a centered mast. The sail was symmetric across the yard, and to shunt, what was previously the top end of the yard was lowered and became the bottom end, reversing the direction of the sail. Proa enthusiast Gary Dierking modified this design further, using a curved yard and a boom perpendicular to the yard. This allows a greater control of the sail shape than the traditional Gibbons rig, while retaining the simple shunting method, and is often referred to as the Gibbons/Dierking rig.

Foils

While a proa is fairly efficient at minimizing the amount of wave drag and maximizing stability, there is at least one way to go even further. The use of underwater foils to provide lift or downforce has been a popular idea recently in cutting-edge yacht building, and the proa is not immune to this influence.

The Bruce foil is a foil that provides a lateral resistance with zero heeling moment by placing the foil to the windward side, angled so the direction of the force passes through the center of effort of the sail. Since proas already have an outriger to the windward side, a simple angled foil mounted on the ama becomes a Bruce foil, making the already stable proa even more stable. Bruce foils are often combined with inclined rigs, which results in a total cancellation of heeling forces. Inclinced rigs are also well suited to the proa, as the direction of incline remains constant during shunting.

Another use of foils is to provide lift, turning the boat into a hydrofoil. Hydrofoils require significant speeds to work, but once the hull is lifted out of the water, the drag is significantly reduced. Many speed sailing designs have been based on a proa type configuration equipped with lifting foils.

Variations on the theme

In a non-traditional variant, first seen among Western yacht racers, the "Atlantic proa" has an ama which is always to the lee side to provide buoyancy for stability, rather than ballast as in a traditional proa. Because the Atlantic ama is at least as long as the main hull, to reduce wave drag, this style can also be thought of as an asymmetric catamaran, that shunts rather than tacking. The first Atlantic proa was the Cheers, designed in 1968 by boat designer Dick Newick for the 1968 OSTAR solo translatlanic race, in which it placed third. Newkirk's designs are primarily trimarans, and the Atlantic proa's buoyant outrigger follows naturally from a conversion of a trimaran from a tacking to a shunting vessel.

Other proa designers blur the lines between Atlantic and Pacific style proas. The Harryproa from Australia uses a long, thin hull to lee, and a short, fat hull, containing the cabin, to windward. This would normally be more like an Atlantic proa, but the rig is on the lee hull, leaving it technically a Pacific design. This and other similar proas place the bulk of the passenger accommodations on the ama, in an attempt to make the vaka as streamlined as possible, and put much of the mass in the lee side to provide a greater righting moment.

Perhaps the most extreme variants of the proa are the ones designed for pure speed. These often completely discard symmetry, and are designed to sail only in one direction relative to the wind; performance in the other direction is either seriously compromised or impossible. These are "one way" proas, such as world record speed holding Yellow Pages Endeavour, or YPE. While the YPE is often called a trimaran, it would be more correct to call it a Pacific proa, because two of the planing/hydrofoil hulls are in line. This design has been considered by others as well, such as the Monomaran designs by "The 40 knot Sailboat" author Bernard Smith, and has been called a 3-point proa by some, a reference to the 3 point hulls used in hydroplanes. A previous record holding design, the Crossbow II, owned by Timothy Colman was a proa/catamaran hybrid. Crossbow II was a "slewing" catamaran, able to slew her hulls to allow clear airflow to her leeward bipod sail. Although the hulls appeared identical, the boat had all crew and controls, cockpit etc. in her windward hull; the leeward hull was stripped bare for minimal weight.

Speed records

In March 2009, two new sailing speed records were set by vehicles based on the proa concept, one on land, and one on the water.

On March 26, 2009, Simon McKeon and Tim Daddo set a new C class speed sailing record of 50.08 knots over 500 meters in the Macquarie Innovation, successor to their previous record holding Yellow Pages Endeavour, with a peak speed of 54 knots. The record was set in winds of 22 to 24 knots, and came close to taking the absolute speed record on water, currently held by l'Hydroptère. Conditions during the record setting run were less than ideal for the Maquarie Innovation, which is anticipated to have a top speed of 58 knots.[11]

On March 27, 2009, Richard Jenkins set a world windpowered speed record, on land, of 126.1 miles per hour (202.9 kph) in the Ecotricity Greenbird. This broke the previous record by 10 miles per hour (16 kph). The Greenbird is based on an one-way proa design, with a long, thin two wheeled body with a third wheel to the lee acting as an ama. The aka, which is in the shape of a wing, provides a significant amount of downwards force at speed to counter the heeling force generated by the high aspect wing sail.[12][13]

See also

References

- ↑ "Definition of Proa". http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/proa. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ Marchaj, C. A.. Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximize Sail Power. ISBN 0-07-141310-3.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (77 AD). Natural History, Book VI, chapter 24. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137&query=head%3D%23256. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ Emma Helen Blair, James Alexander Robertson, Edward Gaylord Bourne (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803: Explorations by Early Navigators. A. H. Clark Co.. http://books.google.com/books?id=Mn0OAAAAIAAJ&pg=99.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Gondola and its Variants". http://www.veniceboats.com/eng-fleet-boats-gondola.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ↑ "Dictionary". http://www.doge.it/regata/regata50i.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ↑ "History: Drake and Anson". http://www.ixtapa-zihuatanejo.com/info/historia2da.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Henry Coleman Folkard (1870). The sailing boat: a description of English and foreign boats. Longmans & Co., London. pp. 242–249. http://books.google.com/books?id=1lwBAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA242.

- ↑ See Antonio Pigafetta

- ↑ "Gizmo". http://www.duckworksbbs.com/plans/jim/gizmo/index.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-26. "It planed although he didn't use that word because it hadn't been invented yet. I'm wondering if it was the first planing boat?" Jim Michalak

- ↑ "New World Speed Record: Macquarie Innovation breaks 50 - hits 54 knots". Sail-World.com. Sat 28 Mar 2009 GMT. http://www.sail-world.com/USA/New-World-Speed-Record:-Macquarie-Innovation-breaks-50---hits-54-knots/55222.

- ↑ Tony Borroz (March 27, 2009). "Freaky Speeder Rides the Wind to World Record". http://blog.wired.com/cars/2009/03/british-man-set.html.

- ↑ "Greenbird official website". http://www.greenbird.co.uk/.

- Haddon, A. C. & Hornell, James (1997). Canoes of Oceania. Honolulu, Hawaii: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0-910240-19-1.

- Munroe, Ralph Middleton; and Gilpin, Vincent (1930). The Commodore's Story. (New York): Ives Washburn. pp. 279–282.

External links

Sources of information on proas

- Guampedia, Guam's Online Encyclopedia Agadna, Chamorro Canoe Builders

- The Proa File by Michael Schacht.

- German proa website Information and links (mainly in German)

- A summary of American proa designs can be found on Craig O'Donnell's Cheap Pages.

- wikiproa a wiki dedicated to proas. Mostly home build smaller designs.

- A collection of links to Proa-related websites from PacificProa.com

- The University of Guam's Traditional Seafaring Society Webpage Micronesia.

- Canoes in Micronesia by Marvin Montvel-Cohen; Micronesian working papers number 2, University of Guam Gallery of Art, David Robinson, Director, April 1970

- Big collection of photos of ancient proas

- 2001 Marshall Island stamps, showing the Marshallese walap

- Canoe Craze In Marshall Islands, Pacific Magazine, By Giff Johnson. Shows modern kor-kor racers in traditional boats with polytarp sails

- Riwuit pictures, and detailed plans on building and tuning a riwuit

- The Vaka Taumako Project page on Polynesian proas and sailing

- Essay with photos of Kapingmarangi sailing canoes, Caroline Islands.

- Duckworks Magazine article on the R.B. Roosevelt and Monroe proas

Individual proa designs

- hinged vector fin proa

- World of Boats (EISCA) Collection ~ Ra Marama II, Fijian Proa

- Mbuli - A Pacific Proa

- P5 - a 5 m multichine proa

- Harryproa website, detailing history and current developments of the Harry type proas

- Dave Culp's untested unidirectional, single foil proa

- Slingshot and Crossbow I shunting ama trimaran/proas

- Gary Dierking's T2 proa design, showing the Gibbons/Dierking rig

- Cheers, the first Atlantic proa

- Rebuilding Cheers, by Vincent Besin

- Video of Cheers' relaunch in 2006

- Video of Jeremie Fischer's proa Equilibre shunting

- Video of Toroa Micronesian style proa, designed and built by Michael Toy and Harmen Hielkema

- Melanesia, a James Wharram design meant to use materials at hand

- Gizmo, an "experimental" minimalist proa by designer Jim Michalak

| |||||

| |||||