Clipper

A clipper was a very fast sailing ship of the 19th century that had multiple masts and a square rig. They were generally narrow for their length, could carry limited bulk freight, small by later 19th century standards, and had a large total sail area. Clipper ships were mostly made in British and American shipyards, though France, the Netherlands and other nations also produced some. Clippers sailed all over the world, primarily on the trade routes between the United Kingdom and its colonies in the east, in trans-Atlantic trade, and the New York-to-San Francisco route round Cape Horn during the California Gold Rush. Dutch clippers were built beginning in 1850s for the tea trade and passenger service to Java.

Contents

Origin

The term clipper originally applied to a fast horse,[1] and most likely derives from the term "clip" meaning "speed", as in "going at a good clip". The Oxford English Dictionary says its earliest quotation for clipper in English is from 1830. Cutler reports the first newspaper appearance was in 1835, and by then the term was apparently familiar. Clipper bows were distinctively wide and lightly raked forward, which allowed them to rapidly clip through the waves. The cutting notion is also suggested by the other class of vessel built for speed, the cutter. Many people consider the era of clipper ships the "Golden age of sailing".

In the United States, "clipper" referred to the Baltimore clipper, a topsail schooner developed in Chesapeake Bay before the American Revolution. It was lightly armed in the War of 1812, sailing under Letters of Marque and Reprisal, when the type—exemplified by Chasseur, launched at Fells Point, Baltimore in 1814 became known for her incredible speed; the deep draft enabled the Baltimore clipper to sail close to the wind.[2]

The third archetypal clipper, with sharply raked stem, counter stern and square rig, was Annie McKim, built in Baltimore in 1833 by Kennard & Williamson.[3][4] Clippers, running the British blockade of Baltimore, came to be recognized for speed rather than cargo space.

In Aberdeen, Scotland the shipbuilders Alexander Hall and Sons developed the "Aberdeen" clipper bow in the late 1830s: the first was the Scottish Maid launched in 1839.[5] There was a vast clipper trade of tea and other goods from the Far East to Europe.

Clippers were built for seasonal trades such as tea, where an early cargo was more valuable, or for passenger routes. The small, fast ships were ideally suited to low-volume, high-profit goods, such as spices, tea, people, and mail. The values could be spectacular. The Challenger returned from Shanghai with "the most valuable cargo of tea and silk ever to be laden in one bottom".[6] Competition among the clippers was public and fierce, with their times recorded in the newspapers. The ships had short-expected lifetimes and rarely outlasted two decades of use before they were broken up for salvage. Given their speed and manoeuverability, clippers frequently mounted cannon or carronades and were used for piracy, privateering, smuggling, or interdiction service.

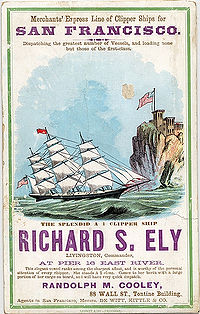

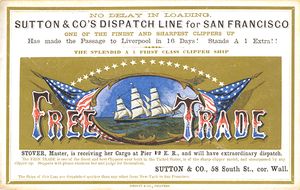

Departures of American clipper ships, mostly from New York City and Boston, Massachusetts to San Francisco, California, were advertised by clipper ship sailing cards, and represented the first pronounced use of color in American advertising art. (Needs Citation)

China clippers and the epitome of sail

The most significant clippers were the China clippers, also called Tea clippers, designed to ply the trade routes between Europe and the East Indies. The last example of these still in reasonable condition is Cutty Sark, preserved in dry dock at Greenwich, United Kingdom, although she suffered extensive damage in a fire on 21 May 2007.

The last China clippers were acknowledged as the fastest sail vessels. When fully rigged and riding a tradewind, they had peak average speeds over 16 knots (30 km/h). The Great Tea Race of 1866 showcased their speed. China clippers are also the fastest commercial sailing vessels ever made. Their speeds have been exceeded many times by modern yachts, but never by a commercial sail vessel. Only the fastest windjammers could attain similar speeds.

There are many ways of judging the speed of a ship: by knots, by day's runs, by port-to-port records. Judged by any test, the American clippers were supreme.

Donald McKay's Sovereign of the Seas reported the highest speed ever achieved by a sailing ship - 22 knots (41 km/h), made while running her easting down to Australia in 1854. (John Griffiths' first clipper, the Rainbow, had a top speed of 14 knots...) There are eleven other instances of a ship's logging 18 knots (33 km/h) or over. Ten of these were recorded by American clippers... Besides the breath-taking 465-mile (748 km) day's run of the Champion of the Seas, there are thirteen other cases of a ship's sailing over 400 nautical miles (740 km) in 24 hours...

And with few exceptions all the port-to-port sailing records are held by the American clippers.

– Lyon, Jane D , p. 138 Clipper Ships and Captains (1962) New York: American Heritage Publishing

The 24h record of the Champion of the Seas wasn't broken until 1984 (by a multihull), or 2001 (by another monohull) [7].

Decline

Decline in the use of clippers started with the economic slump following the Panic of 1857 and continued with the gradual introduction of the steamship. Although clippers could be much faster than early steamships, they depended on the vagaries of the wind, while steamers could keep to a schedule. The steam clipper was developed around this time, and had auxiliary steam engines which could be used in the absence of wind. An example was Royal Charter, built in 1857 and wrecked on the coast of Anglesey in 1859. The final blow was the Suez Canal, opened in 1869, which provided a great shortcut for steamships between Europe and Asia, but was difficult for sailing ships to use. With the absence of the tea trade, some clippers began operating in the wool trade, between Britain and Australia.

Although many clipper ships were built in the mid-19th century, Cutty Sark was, perhaps until recently, the only survivor. Falls of Clyde is a well-preserved example of a more conservatively designed, slower contemporary of the clippers, which was built for general freight in 1878. Other surviving examples of clippers of the era are less well preserved, for example the oldest surviving clipper City of Adelaide[8] (a.k.a. S.V. Carrick).[9]

During the first and second World Wars, several battleships and aircraft carriers were built with a "clipper bow" for improved hydrodynamic efficiency. The clipper bow on carriers was an American peculiarity, Japanese ships did not feature it and British ships had the similar but differently-shaped "hurricane bow," whose purpose was, like the clipper bow, to improve hydrodynamic efficiency and, unlike the clipper bow, protect the hangar deck from spray.

Modern clipper ships

In 2000, two new clippers were built: Stad Amsterdam and Cisne Branco (Brazilian Navy). They are not replicas of any one ship, but an attempt to combine what their builders consider the "best" qualities of clipper ships.

“They [clipper ships] still hold their own for long sea voyages.

There is a limit to the use of steam, and it is reached when the distance to be travelled makes the cost of coal and the space it occupies greater than the value of the cargo will warrant.

Until some new motive power replaces steam, or steam is replaced by the use of petroleum or other concentrated fuel, the clipper still has an occupation, and the hearts of all old-time skippers will be gladdened by the sight of her white wings upon the seas.” [10]

– Chadwick, F.E., Ocean steamships ... (1891) New York: C. Scribner's Sons, p. 225-226

Notable clipper ships

Three famous clipper ships which can be seen as models are Comet, Snow Squall, and Flying Cloud.

- Plans for model of clipper ship Sea Witch, Popular Science, 1933

- Building model of clipper ship Swordfish from 1955 plastic kit, YouTube video

- Plans for model of clipper ship Great Republic, Popular Science, 1935

- McCann, E A (1995). How to make a clipper ship model. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486285801. Plans for model of Sovereign of the Seas.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

People associated with clipper ships

Ships

Footnotes

- ↑ "Clipper". New International Encyclopaedia. 5. Dodd Mead and Company. 1909. pp. 39. http://books.google.com/books?id=qycVAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22clipper%20ship%22&lr=&as_drrb_is=b&as_minm_is=0&as_miny_is=&as_maxm_is=0&as_maxy_is=&num=100&as_brr=4&pg=PA39#v=onepage&q=%22clipper%20ship%22&f=false. Retrieved Mar. 6, 2010. "Clipper ... probably connected with Dutch klepper, fast horse".

- ↑ Villiers 1973.

- ↑ Dear, I.C.B., & Kemp, Peter, eds. Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (Oxford University Press, 2005).

- ↑ Website "bruzelius.info". Accessed 30 March 2009.

- ↑ http://www.aberdeenships.com/sb_alexander_hall.asp

- ↑ Forbes, Allan; Ralph Mason Eastman, State Street Trust Company (Boston, Mass.) (1952). Yankee ship sailing cards.... State Street Trust Co..

- ↑ http://www.sailspeedrecords.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=81&Itemid=21

- ↑ City of Adelaide website - Condensed History

- ↑ Jim Carrick. "The Future of the S.V. Carrick". History Scotland magazine. http://www.historyscotland.com/features/svcarrick.html.

- ↑ Rideing, William H (1891). Ocean steamships; a popular account of their construction, development, management and appliances. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.. pp. 225–226. http://books.google.com/books?id=1ylw5sqwJwoC&dq=clipper&lr=&num=100&as_brr=4&pg=PA225#v=onepage&q=clipper&f=false.

References

- Carl C. Cutler, Greyhounds of the Sea (1930, 3rd ed. Naval Institute Press 1984)

- Alexander Laing, Clipper Ship Men (1944)

- David R. MacGregor, Fast Sailing Ships: Their Design and Construction, 1775-1875 Naval Institute Press, 1988 ISBN 0-87021-895-6 index

- Oxford English Dictionary (1987) ISBN 0-19-861212-5.

- Bruce D. Roberts, Clipper Ship Cards: The High-Water Mark in Early Trade Cards, The Advertising Trade Card Quarterly 1, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 20-22.

- Bruce D. Roberts, Clipper Ship Cards: Graphic Themes and Images, The Advertising Trade Card Quarterly 1, no. 2 (Summer 1994): 22-24.

- Bruce D. Roberts, Museum Collections of Clipper Ship Cards, The Advertising Trade Card Quarterly 2, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 22-24.

- Bruce D. Roberts, Selling Sail with Clipper Ship Cards, Ephemera News 19, no. 2 (Winter 2001): 1, 11-14.

- Villiers, Capt. Alan, 1973. Men, Ships and the Sea (National Geographic Society)

- Chris and Lesley Holden (2009). Life and Death on the Royal Charter. Calgo Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-9545066-2-9.

Further reading

- Crothers, William L (1997). The American-built clipper ship, 1850-1856 : characteristics, construction, and details. Camden, ME: International Marine. ISBN 0070145016. -- Comprehensive reference on the design and construction of American-built clipper ships. Contains numerous drawings, diagrams, and charts, with examples of how each design feature varies in different ships.

- Westward by Sea: A Maritime Perspective on American Expansion, 1820-1890, digitized source materials from Mystic Seaport, Library of Congress American Memory

- The Era of the Clipper Ships, illustrated Web narrative of clipper development

- Clark, Arthur H. (1910). The Clipper Ship Era, An Epitome of Famous American and British Clipper Ships, Their Owners, Builders, Commanders, and Crews, 1843-1869. Camden, ME: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. http://books.google.com/books?id=HVYuAAAAYAAJ&dq=the%20clipper%20ship%20era%20clark&lr&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Lubbock, Basil (1933, reprinted 1967). The Opium Clippers. Boston, MA: Charles E. Lauriat Co.. ISBN 10718065.

- Lubbock, Basil (1984). The China clippers. The Century seafarers. London: Century. ISBN 9780712603416.

- Howe, Octavius T; Matthews, Frederick C. (1926-1927, 1986 reprint ed.). American Clipper Ships 1833-1858. Volume 1 and 2. Salem, MA; New York: Marine Research Society; Dover Publications. ISBN 04865152.

External links

- City of Adelaide Clipper Ship, one of the few surviving clippers

- Clipper Ship cards

- Clipper Ship Cards (from The Trade Card Place)

- Clipper Ship Cards, Flikr collection

- Tea Clippers, UK Tea Council

- The Shipslist: Baltimore Clipper

- "Baltimore Clippers - Pirates of the Chesapeake": career of Chasseur

- The Telanak

- Clippers on DelfSail 09 - Clippers Delfsail 09 by photographer David Dekel.

- Clippers race Den Helder 08 - Clippers Den Helder 08 by photographer David Dekel.

- Endeavour Project - Clippers on Endeavour Tall Ships Project.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||

be:Кліпер bs:Kliper bg:Клипер (кораб) ca:Clíper cs:Klipr da:Klipper de:Klipper es:Clíper fr:Clipper ko:클리퍼 io:Klipero id:Kliper is:Klippari it:Clipper (nave) nl:Klipper ja:クリッパー (船) no:Klipper pl:Kliper (żaglowiec) pt:Clipper (veleiro) ru:Клипер (парусное судно) simple:Clipper sk:Kliper (plachetnica) sr:Клипер sh:Kliper fi:Klipperi sv:Klipperskepp uk:Кліпер